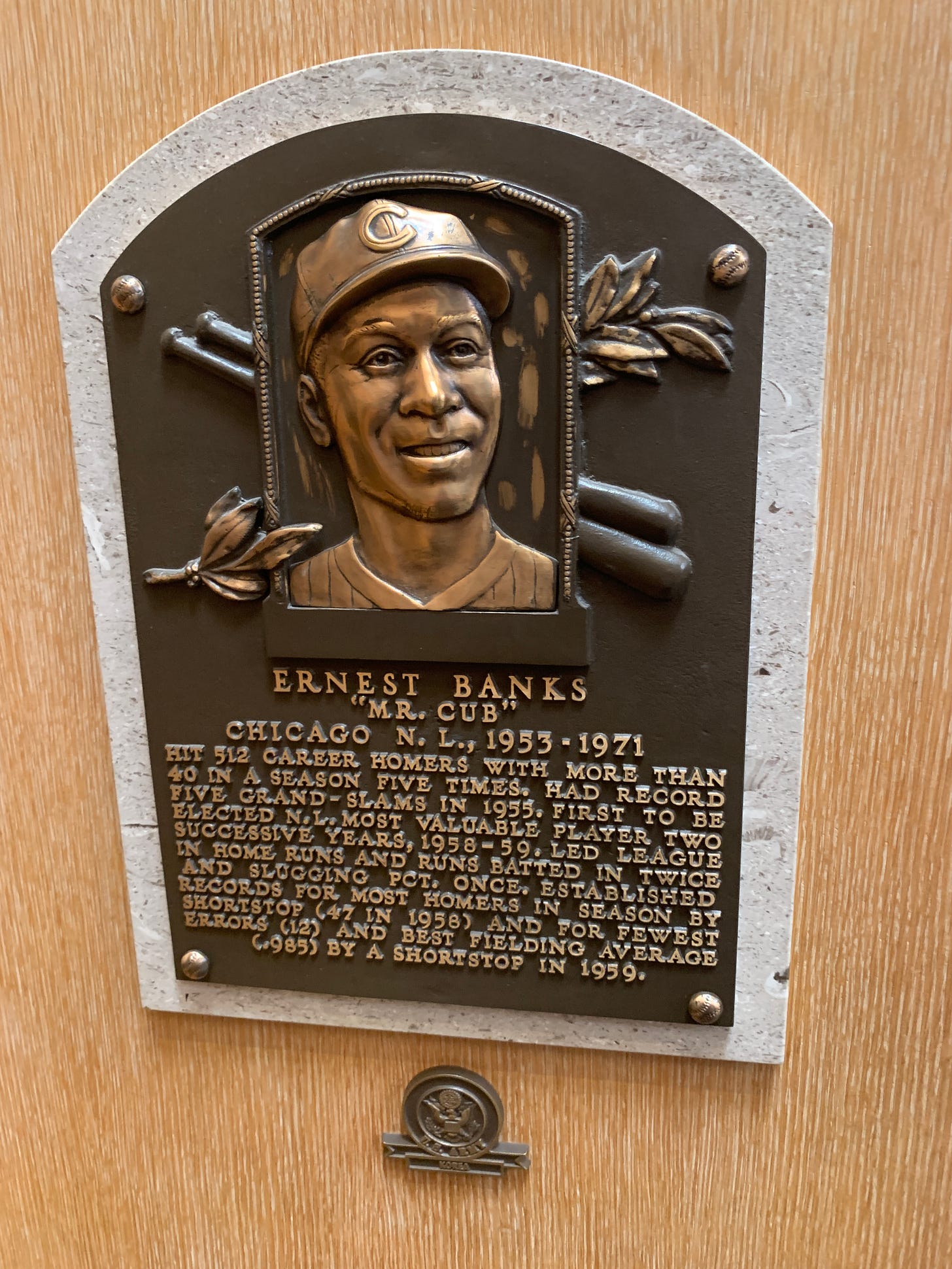

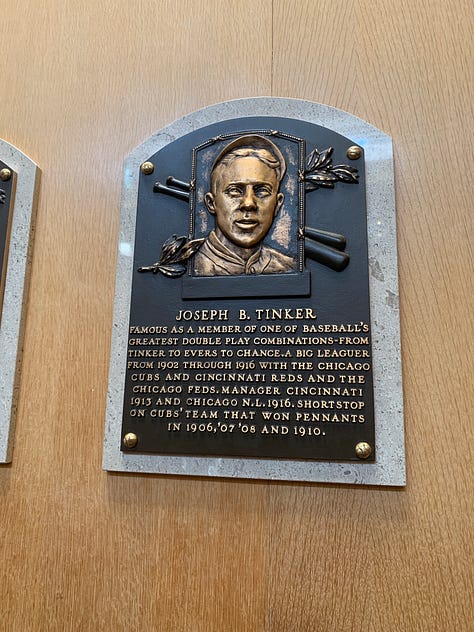

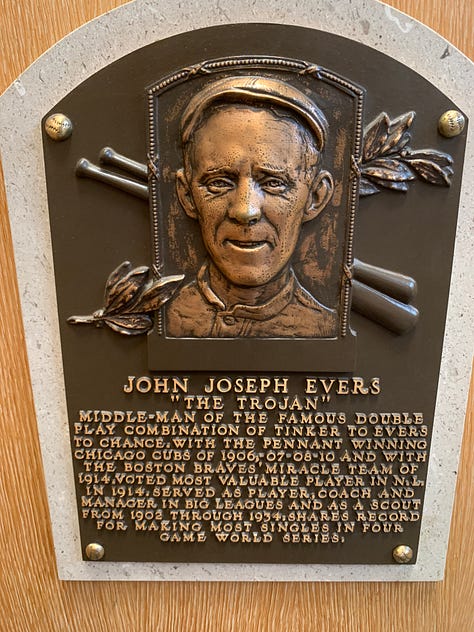

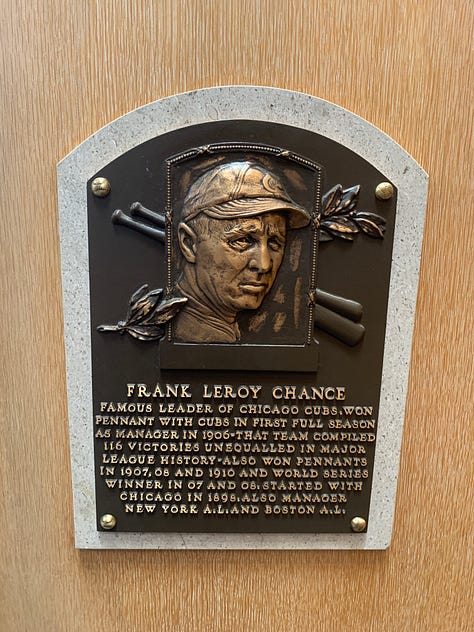

Tinker to Evers to Chance

Happy Opening Day!

Another bonus edition of my newsletter, this time focused on baseball in honor of Opening Day. I’ve never been a huge baseball fan, I enjoy the game and its place in culture, but I never felt the fervor toward it that I have for basketball or even the NFL at one time.

Still, hard to beat a day at the ballpark with some friends. I also think hot dogs are the platonic ideal of concession stand offerings. I love a hot dog with the basics like mustard and onions and also more elaborate toppings and buns. But for my money, the Chicago dog can’t be beat. I’m a little biased as I was born just outside of Chicago in Maywood, Illinois. I can hang my hat on sharing a hometown with John Prine and Chairman Fred Hampton. The location of my birth is one reason I am ostensibly a Cubs fan, albeit a super casual one. The other is familial obligation. My late-grandfather on my father’s side of the family was a Cubs fan, so I was one as well.

Here is a column I wrote for a sports journalism class I had my senior year that I repurposed for a column I wrote in the summer of 2011.

The five stages of grief for a Cubs fan

Springtime — a time when a young man’s fancy turns to thoughts of love and futility for the Chicago Cubs’ current season.

Being a Cubs fan entails going through the five stages of grief every season; and much like the children of parents who expect nothing less than perfection, they always seem to find a way to disappoint you.

Stage One: Denial

This typically occurs just before the All-Star Break when the club’s record is hovering close to .500.

You tell yourself, “There’s plenty of time to turn this season around. We’re not the worst in our division and there’s a good chance we might be able to get the Wild Card slot. We’ll finally bring the Commissioner’s Trophy to Wrigley.”

Stage Two: Anger

The Cubs occasionally get their act together following the All-Star Break; but once the calendar turns to September, they become a team of gibbering idiots to whom baseball is a foreign concept.

You, the irate Cubs fan, attempt to smuggle several goats into Wrigley in order to placate the angry spirit of Billy Sianis’ goat. After you post bail and begin completing your community service, you enter the next stage of grieving: bargaining.

Stage Three: Bargaining

It’s quite clear at this point that the Cubs have a snowball’s chance in hell of making the playoffs. Having your team mathematically eliminated from playoff contention will not deter you.

“That’s what arcane rituals with forces beyond the comprehension of mortal man are for,” you say to yourself.

You’ll make a stop at your local occult bookstore and begin searching for a way to summon a Lovecraftian horror into your rumpus room.

The ceremony begins and you chant, “Ph’nglui mglw’nafh Cthulhu R’lyeh wgah’nagl fhtagn.”

Suddenly an eldritch figure appears next to your commemorative Cubs beer stains. Your mind screams in horror at something man was not meant to see.

“Greetings, O Dread Cthulhu, I have awoken you to ask for a small favor, can you arrange it for the Cubs to win the World Series?” you ask in a quavering voice.

“That,” says in a voice that causes babies scream in the night, “is beyond even my power. Besides, I’m a Yankees fan. Bother me no more lest I swallow your soul.”

Realizing that not even a creature beyond comprehension can help your team, you enter the penultimate stage.

Stage Four: Depression

Once again the Cubs have let you down. What was a promising season spiraled into one of shame and regret. The Cubs are a metaphor for your life. Their Sisyphean struggle to win another World Series matches your own ineffective attempts at sorting out your life.

Like all Cubs fans, you’re probably a heavy drinker. It’s the only way to get through the long stretches of humiliation.

You start drinking even more and taking in harder stuff. Maybe you start doing coke, chopping it up on the jewel case of Tonight’s The Night while it plays in the background.

Your friends and family start to worry about your mental health and stage an intervention. It’s when you leave the mental health facility that you enter the final stage.

Stage Five: Acceptance

The scars of the past season have healed and you look hopefully toward the coming season.

The Cubs may have been frustrated last year, but there’s a change in coaches and new talented players who are sure to change things for the better. You smile at the nurses as they wheel you out.

“There’s always next year,” you say.

“Of course, Mr. Caray,” says the nurse with a patronizing smile. “Nurse Ratched, double his Thorazine drip.”

After the Cubs made it back to the World Series in 2016, I wrote this piece about my relationship with my grandfather and how baseball was one way we were able to bridge the decades between us.

For Gene

As far as sports go, baseball was never one of my great loves. But I had an appreciation for the game and its place in the fabric of the culture. I understood the ballpark experience and the mythos and history.

Sometime in 1993 or 1994, I attended a Cubs game with my father and his father at Wrigley field. I don’t recall the particulars of the game, but I ended up with a miniature souvenir bat.

My parents got divorced in 1996 and my dad stopped being a part of my life.

My grandfather, a retired pharmacist and Navy veteran, became a surrogate father.

There were 71 years between us, it was a gap that was hard to bridge, but we tried to bridge it, talking about his trips to the senior center in Weiser, Idaho and also the weather. Basic, low stakes topics. When I studied Latin, he’d talk about translating Caesar’s chronicling of the Gallic Wars. And when I was in college he’d tell me about going on dates to the movies. A dime got two people in, he’d tell me.

During college, I’d call him on the phone a few times a month. He’d send me some pocket money once a month.

When he would come for a visit during the summer, I recall seeing him snoozing on the couch, reclined, his leather shoes on the ground, WGN broadcast of an afternoon game droning on in the background. That hazy sort of feeling one gets when the mercury begins to rise in the middle of July.

I casually followed the Cubs, as a point of discussion for us. When they lost or fell out of the playoff race, he’d always say, “But that’s all right.”

It was a world view I came to admire, it reminded me of the very famous refrain of So it goes.

He became quite ill my senior year of college. I was nervous, but he was pretty spry for a 92 year old man. I think he knew his time was short during our last phone conversation. Neither of us wanted it to end. There was an air of finality. There was also something he wanted to convey, but didn’t have the words for. Still, I knew what he meant.

He died days before Thanksgiving, a holiday he loved. He and my grandmother would visit us for it. And after she passed, he would visit.

Losing him felt like losing my father.

He was born in 1918, ten years after the Cubs had last won a World Series. Their last appearance came shortly after he left the Navy. My grandmother, his wife of more than 50 years, died a month before the Bartman incident.

I miss him terribly, especially right now.

Tonight…

He would have been overjoyed tonight.

Composer Charles Ives was a big baseball fan and his love of the game sometimes came through explicitly in his compositions such as “Some South-Paw Pitching,” a piano exercise designed to improve the left hand.