Neil Young understands the burden of being a survivor—the guilt of what ifs, counterfactuals that point to a different outcome. A series of tragedies sparked a run of work that plumbs the depths of human misery with occasional flickers of hope and optimism that are soon extinguished. If side one of On The Beach represents embers of hope, side two represents those hopes flickering as the forces of the world threaten them.

The shift in style, looser and more ragged in production and playing, was Young’s response to the success of “Heart of Gold.”

“This song put me in the middle of the road. Traveling there soon became a bore, so I headed for the ditch. A rougher ride but I saw more interesting people there.”

Neil Young’s detour to the ditch can be traced back to Harvest, the same album on which “Heart of Gold” appeared.

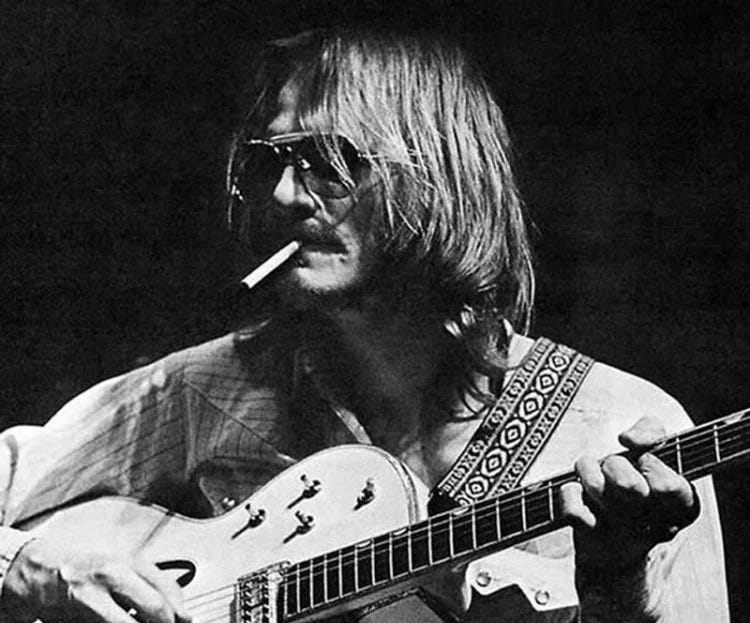

That album made him a star and also included “The Needle And The Damage Done,” a song inspired by the brilliant but troubled songwriter and Crazy Horse guitarist Danny Whitten.

Danny, Phil & Kurt

“Danny Whitten was the focal point of Crazy Horse, but he was also the fault line that ran through it. Like many a troubled genius, the greatness of his art was partly a product of his own tragic life. He left us with a slice of magic in this album but also with the thought that he could have given us so much more had he given himself a chance to,” Young said.

Whitten was born in Columbus, Georgia. Early on in his musical career, he was a member of a doo-wop group called Danny and the Memories. Also in the group were future Crazy Horse members Billy Talbot and Ralph Molina. After moving to the Bay, the group shifted styles and wore a new moniker: The Psyrcle. Like many other bands active in San Francisco at the time, they played psychedelic-accented folk music.

The trio became a sextet and became known as The Rockets. Neil Young — recently departed from Buffalo Springfield and fresh off his self-titled debut album — started jamming with the band and discussed recording music with Talbot, Whitten, and Molina. Two more name changes later and the group found one that stuck: Crazy Horse.

They backed Young on Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, the first album of a monumental run that continued into the 1970s. Whitten’s vocals are most prominent on the 45 version of “Cinnamon Girl.” He takes the high harmony, while Young goes low.

In the liner notes for Decade, Young gave a cryptic answer about the tune’s inspiration: “Wrote this for a city girl on peeling pavement coming at me thru Phil Ochs eyes playing finger cymbals. It was hard to explain to my wife.”

The woman in question was likely Jean Ray of the folk duo Jim and Jean.

Ochs was a songwriter Young admired a great deal. “‘Melodically speaking, Phil Ochs was a big influence on me,’ Young told deejay Tony Pig in 1969. ‘I really think Phil Ochs is a genius…. He’s written fantastic, incredible songs—he’s on the same level as Dylan in my eyes.’”- Jimmy McDonough, Shakey: Neil Young’s Biography

In 2013, Young performed “Changes” at Farm Aid and, while introducing the song, spoke of Ochs as another singer gone before his time. Ochs was only 35 when he killed himself.

“I was talking backstage with Pete [Seeger] before he came out here and [he] told me a tale about this friend of his, how we lost this friend a long time ago, because life is short. And he killed himself and Pete talked to him a few days before that happened and he was saying ‘You know I really…I wish I had done something more to stop that from happening.’ And I said “Well, you know don’t worry about that, there’s nothing you can do about it, because that kind of thing happens all the time,” Young said.

“That happened to me. I had a friend who was a singer and he was great. And he reached out to me and I tried to get back to him through his office. I tried for days and days and finally I gave up. A couple of days later he blew his head off. So life is short and you can regret things,” Young said, alluding to the death of Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain.

Cobain quoted Young’s “My My, Hey Hey (Out of the Blue)” in his suicide note.

While Young and Cobain never met, Young saw many parallels between Cobain and Whitten and tried to contact him.

“I like to think that I possibly could have done something,' he says, concentrating on finding the right words. 'I was just trying to reach him. Trying to connect up with him.'

He pauses and thinks again. 'It's just too bad I didn't get a shot. I had an impulse to connect. Only when he used my song in that suicide note was the connection made. Then, I felt it was really unfortunate that I didn't get through to him. I might've been able to make things a little lighter for him, that's all. Just lighten it up a little bit.'" - Burhan Wazir, Neil Young: the quiet achiever, The Sydney Morning Herald, 2002

Cobain’s suicide bothered Young. Each had admired the other’s work, and yet another loss inspired the title track of Young’s 1994 album Sleeps With Angels. It touched on similar thematic ground, as noted in a review of the album in Broken Arrow, a Neil Young fanzine.

“First, there are the obvious similarities between ‘Sleeps With Angels’ and ‘Tonight's The Night,’ which have been well publicized, such as Kurt Cobain's suicide being Sleeps With Angels's title track influence. This parallels Crazy Horse guitarist Danny Whitten's heroin overdose and its shadow on Tonight's The Night. Thematically, Sleeps With Angels and Tonight's The Night are very similar - dark and brooding. But where Tonight's The Night was loose, raw, ragged, edgy and over the top, Sleeps With Angels is tightly wound, controlled, and hypnotic. The refrain of ‘Tonight's The Night’ has been replaced with a repeated ‘Too soon, Too Late’ in ‘Sleeps With Angels’. There are other similarities between the late Danny Whitten and Kurt Cobain tragedies besides their grizzled blond looks, fondness for heroin, tortured singer/songwriter/guitarist artist and death before age 30. More on Danny Whitten in the Broken Arrow article by Scott Sandie, Issue #87." - Keith Bonney, “Sleeps With Angels: The Sequel to Tonight's The Night?”, Broken Arrow issue #57

“What that suicide has done is return me to my roots. Makes me go back and investigate where I started. Where I came from. Why am I here and why is he not here? Does my music suffer because I survived? Things like that.”- Jimmy McDonough, Shakey: Neil Young’s Biography

There were many parallels between Whitten and Cobain. They sported dirty blonde locks and resembled each other physically. If they had looked at each other face to face, holding their guitars, they would have resembled a mirror image of the—Cobain was ambidextrous but chose to play southpaw—Duck Soup for opioid addicts.

Addiction was another aspect they shared—heroin to dull physical pain. Whitten used horse to dull the pain of rheumatoid arthritis. Perhaps it was for emotional pain as well. Whitten's parents split when he was young. He and his sister lived with their mother, who supported them by working long shifts as a waitress. She remarried when he was nine, and the family moved to Ohio.

Both plagued Cobain. He suffered from a chronic stomach condition and had scoliosis, which was worsened by playing guitar with his left hand as his spine curved slightly to the right. Had he played with his right hand, his problem might have corrected itself. The weight of the guitar strap over the right shoulder instead of the left exacerbated the problem. The cause of the stomach pain was pinned on a pinched nerve in his spine

“My body is damaged from music in two ways: l not only has my stomach inflamed from irritation, but I have scoliosis. I had minor scoliosis in junior high, and since I've been playing the guitar ever since, the weight of the guitar has made my back grow in this curvature. So when I stand, everything is sideways. It's weird.” - Kurt Cobain, in an interview with Jon Savage

Had he played right-handed, it’s possible he wouldn’t have needed to numb the pain in his body. Or perhaps given the rough emotional waters he’d had to navigate since he was a child, heroin might have been in his future regardless.

“The Unplugged music bothered me a lot. Contrary to what people said at the time, he didn’t sound dead, or about to die, or anything like that. As far as I could tell, his voice was not just alive but raging to stay that way.” - Rob Sheffield, Love Is A Mixtape: Life and Loss, One Song at a Time.

“But when I listen to Kurt, he’s not ready to die, at least not in his music—the boy on Unplugged doesn’t sound the same as the man who gave up on him. A boy is what he sounds like, turning his private pain into teenage news. He comes clean as a Bowie fan, up to his neck in Catholic guilt, a Major Tom trying to put his Low and his Pin Ups on the same album, by mixing up his favorite oldies with his own folk-mass confessionals. I hear a scruffy sloppy guitar boy trying to sing his life. I hear a teenage Jesus superstar on the radio with a song about a sunbeam, a song about a girl, flushed with the romance of punk rock. I hear the noise in his voice, and I hear a boy trying to scare the darkness away. I wish I could hear what happened next, but nothing did.” - Rob Sheffield, Love Is A Mixtape: Life and Loss, One Song at a Time.

I see a similar level of life left to live in Phil Ochs’ final live recordings, like Gunfight at Carnegie Hall, recorded in 1970, and Live Again!, recorded in 1973.

Whitten, Ochs, and Cobain still had something to give, yet they died young and in despair. Ochs and Cobain killed themselves in early April. Cobain on the fifth in 1994 and Ochs on the ninth in 1976. Cobain’s body was discovered three days after he died, he did not rise again. Cobain had just turned 27 in February and Ochs had turned 35 the previous December

Whitten’s death came late in the fall, on November 18th, 1972. Six days after Young had turned 27. Whitten was 29. Songwriters of immense talent, with so much more they could have done, whether making music or just living.

Cobain killed himself with a shotgun blast to the head; he was high on heroin and Valium when he took his life, and there remains some speculation if it was a fatal dose.

Ochs’ alcoholism and bipolar disorder fed his despair. The tragedies he suffered personally and professionally only added to his anguish. When his final studio album, Greatest Hits, ended with “No More Songs,” he meant it.

“By Phil's thinking, he had died a long time ago: he had died politically in Chicago in 1968 in the violence of the Democratic National Convention; he had died professionally in Africa a few years later when he had been strangled and felt that he could no longer sing; he had died spiritually when Chile had been overthrown and his friend Victor Jara had been brutally murdered; and, finally, he had died psychologically at the hands of John Train.” - Michael Schumacher, There But For Fortune: The Life of Phil Ochs.

You live long enough, and you end up outliving people. Sometimes, that guilt is hard to live with. You question why it was them and not you and wonder at the unfairness of life, that better people than you wound up six feet under or ashes scattered to the winds.

Deaths of despair were no stranger to me growing up in the Rust Belt. At my first newspaper job, it was rare to go a day without hearing about an overdose on the police scanner in the newsroom. I’ve lost at least two friends to heroin overdoses. If I held any anger, it was directed inward. I am angry at myself for not doing more to ease their pain and offer my compassion and understanding. Such is the way of survivor’s guilt. You blame yourself for what might have been and contort yourself into holding painful positions as punishment for the crime of not doing enough, the sin of living while others did not.

Young blames himself for Whitten’s death, which is another reason Cobain’s suicide affected him so much, especially with quoting one of his songs in his final note. It shook him to his core.

“I don't wanna talk about that. I just don't know what to say. Obviously his interpretation should not be taken to mean there's only two ways to go and one of them is death.” - Neil Young, “Reflective Glory” by Steve Sutherland & Kevin Cummins, New Musical Express, July 10, 1995

I’ll Get By

“Cinnamon Girl” is one of three songs Young wrote while suffering from a high fever; the other two were “Down By The River” and “Cowgirl In The Sand,” which all remain staples of his live sets.

Whitten had started using heroin to help manage the pain he felt from rheumatoid arthritis. He got addicted, and his heavy drug use was partly the reason Crazy Horse did not take part in the recording of After The Gold Rush. Whitten plays guitar on a few songs on the album and contributed harmony vocals on other songs.

Young wrote “The Needle And The Damage Done” during this era. In the liner notes for it in Decade, Young wrote, "I am not a preacher, but drugs killed a lot of great men."

Despite his drug troubles, Whitten continued making music. He wrote five cuts on Crazy Horse’s self-titled debut, including “Downtown,” a version titled (Come On Baby Let's Go) Downtown" would appear on Tonight’s The Night. It’s the most joyous song on that album, despite being about a heroin addict trying to score smack.

Also on that album is “I Don’t Want To Talk About It,” a heartbreaking ballad that was covered by Rod Stewart and Everything But The Girl. It was a song that showed Whitten’s potential as a songwriter, a sad capstone on a career and life cut far too short.

His addiction led to being dismissed from Crazy Horse by Molina and Talbot. But he was invited to play with Young as a member of The Stray Gators, the group that backed Young on Harvest and would later play on Time Fades Away, the first album in The Ditch Trilogy.

Whitten lagged in learning the rhythm guitar parts, and he was out of sync with his bandmates. Young made the difficult decision to cut Whitten loose. He had more at stake for the Harvest tour after the success of that album and After The Gold Rush. Whitten was fired from the band and given $50 and a plane ticket back to Los Angeles from San Francisco. He died that night after mixing Valium with alcohol. The former was to help soothe the arthritis in his knees, and the latter was to help him off heroin.

“We were rehearsing with him and he just couldn't cut it. He couldn't remember anything. He was too out of it. Too far gone. I had to tell him to go back to L.A. 'It's not happening, man. You're not together enough.' He just said, 'I've got nowhere else to go, man. How am I gonna tell my friends?' And he split. That night the coroner called me and told me he'd died. That blew my mind. Fucking blew my mind. I loved Danny. I felt responsible. And from there, I had to go right out on this huge tour of huge arenas. I was very nervous and ... insecure,” said Young.

He blamed himself for Whitten’s death for years.

“Danny just wasn't happy,” Young said. “It just all came down on him. He was engulfed by this drug. That was too bad. Because Danny had a lot to give, boy. He was really good.”

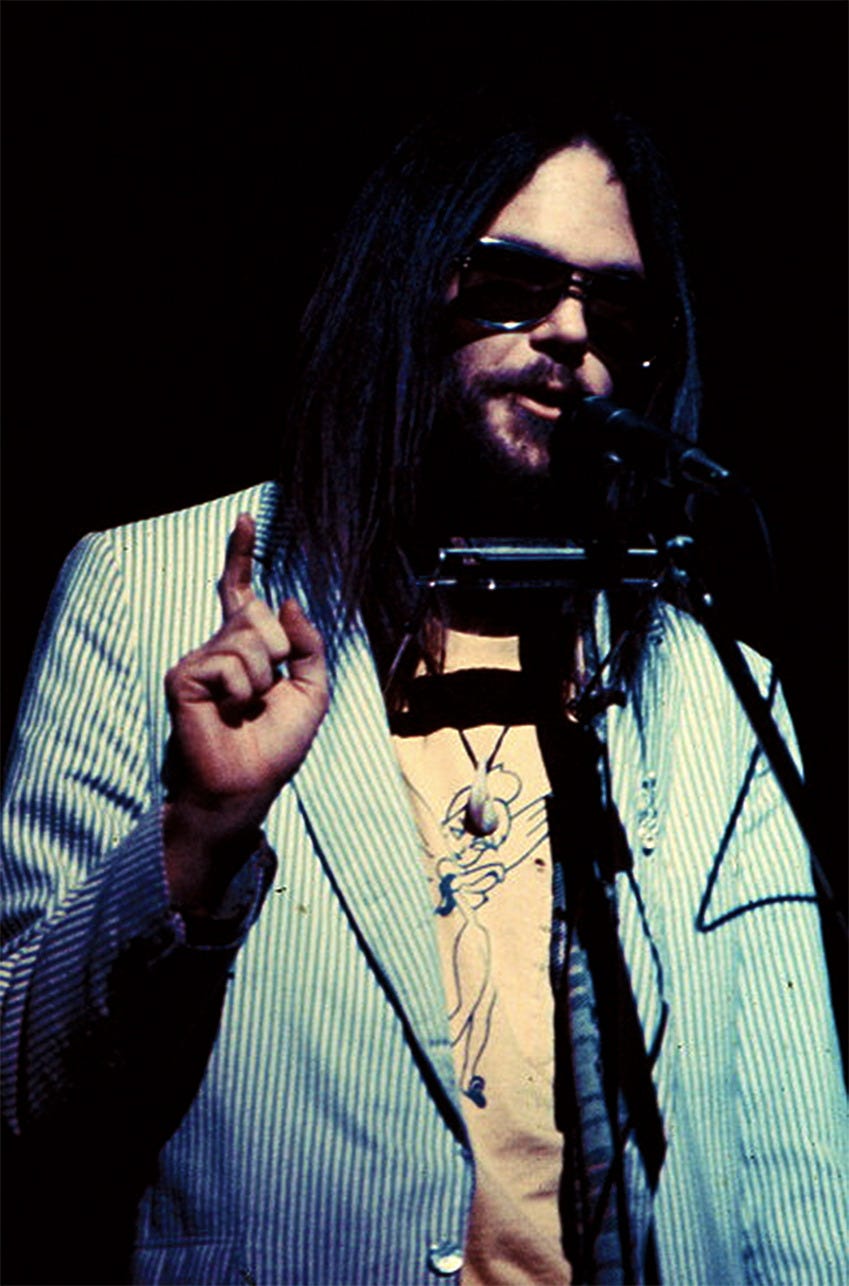

Time Fades Away

The tour was not without its share of issues; Young was abusing alcohol and developed a throat infection during the last days of the tour.

Young has little love lost for the album, which was out of print for decades before finally getting released in 2014 as part of a limited edition vinyl box set that also included On The Beach, Tonight’s The Night, and Zuma. It was part of a CD box set released in 2017 and was made available separately in 2022, just in time for the 50th anniversary of the album’s release.

“Time Fades Away. No songs from this album are included here. It was recorded on my biggest tour ever, 65 [sic] shows in 90 days. Money hassles among everyone concerned ruined this tour and record for me but I released it anyway so you folks could see what could happen if you lose it for a while. I was becoming more interested in an audio verite approach than satisfying the public demands for a repetition of Harvest,” wrote Young in the original, unreleased liner notes for Decade.

Tonight’s The Night

Young’s next album plunged to greater depths of sorrow and would be shelved for two years. Tonight’s The Night was inspired by the death of Whitten and Bruce Berry, a roadie for Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. Whitten had introduced Berry to heroin, and it ruined his life. He died of a heroin and cocaine overdose on June 4, 1973. He was only 22. Berry, brother of Jan Berry or surf rock duo Dan & Jean, had gotten his start working for Studio Instrument Rentals, which is how he met CSNY.

“At S.I.R. we were playing, and these two cats who had been a close part of our unit – of our force and our energy – were both gone to junk. Both of them O.D.'d, and we're playing in a place where we're getting together to make up for what is gone and try to make ourselves stronger and continue. Because we thought we had it with Danny Whitten – at least I did. I thought that I had a combination of people that could be as effective as groups like the Rolling Stones had been. Just for rhythm, which I'm really into. I haven't had that rhythm for a while and that's why I haven't been playing my guitar; because without that behind me I won't play. I mean you can't get free enough. So I've had to play the rhythm myself ever since Danny died,” said Young in a 1975 interview with Creem.

“Tequila and hamburgers. That was the input,” said Young about what fueled the making of that album. He’d started drinking tequila during the tour that produced Time Fades Away.

An early release of the album contained this message “I'm sorry. You don't know these people. This means nothing to you.”

The liner notes were full of cryptic messages, including a Dutch review of a show performed in Amsterdam.

The liner notes include a letter directed to a mysterious figure dubbed Waterface. “Hello Waterface” appears in the run-out groove on Side 1 and “Goodbye Waterface” in the same place on Side 2. It would be easy to assume Waterface refers to Whitten, particularly because of the line “Tell Waterface to put it in his lung and not in his vein” in the liner notes.

Young said that “Waterface is the person writing the letter. When I read the letter, I’m Waterface. It’s just a stupid thing—a suicide note without the suicide.”

“Tonight's The Night is like an OD letter. The whole thing is about life, dope and death. When we played that music we were all thinking of Danny Whitten and Bruce Berry, two close members of our unit lost to junk overdoses. The Tonight's The Night sessions were the first time what was left of Crazy Horse had gotten together since Danny died. It was up to us to get the strength together among us to fill the hole he left. The other OD, Bruce Berry, was CSNY's roadie for a long time. His brother Ken runs Studio Instrument Rentals, where we recorded the album. So we had a lot of vibes going for us. There was a lot of spirit in the music we made. It's funny, I remember the whole experience in black and white. We'd go down to S.I.R. about 5:00 in the afternoon and start getting high, drinking tequila and playing pool. About midnight, we'd start playing. And we played Bruce and Danny on their way all through the night. I'm not a junkie and I won't even try it out to check out what it's like. But we all got high enough, right out there on the edge where we felt wide open to the whole mood. It was spooky. I probably feel this album more than anything else I've ever done,” Young said in a 1975 Rolling Stone interview with Cameron Crowe.

The record company was not happy with the album, not the last time Young would draw the ire of a label for making music deemed uncommercial.

“When I handed it to Warner's, they hated it. We played it ten times as loud as they usually play things and it was awful. I mean, can you imagine listening to it at 1:00 in the afternoon in some corporate office? Well, I wasn't trying to make a masterpiece. I was trying to capture a moment. I didn't want to clean it up. I don't want the Carpenters to play Tonight's The Night. The album was recorded very high on tequila, and we did the same thing when we went out on the road with the Tonight tour. For me, it's very much like being an actor. I try to live the songs in my mind. Tonight's The Night was a story of death and dope. It was about a sleazy, burned-out rock star just about to go, about what fame and crowds do to you. I had to exorcise those feelings. I felt like it was the only chance I had to stay alive,” Young said in a 1978 interview with Tony Schwartz for Newsweek.

On The Beach

The third album of the trilogy was the one released second. Stylistically, closing out the trilogy with that album makes more sense. While filled with despair, it has a lighter tone than Tonight’s The Night. The first side is pretty optimistic relative to the rest of Young's music during this period, though the second half isn’t exactly sunshine and rainbows and quite harrowing at times. It is melancholic while avoiding the full nihilism of Tonight’s The Night. Young borrowed the melody of “Lady Jane” for “Borrowed Tune” and does another bit of musical borrowing with “Ambulance Blues,” which features a melody similar to Bert Jansch’s “Needle of Death.”

“As for acoustic guitar, Bert Jansch is on the same level as Jimi [Hendrix]. That first record of his is epic. It came from England, and I was especially taken by 'Needle of Death', such a beautiful and angry song. That guy was so good. And years later, on On the Beach, I wrote the melody of 'Ambulance Blues' by styling the guitar part completely on 'Needle of Death'. I wasn't even aware of it, and someone else drew my attention to it,” said Young in a 1992 article in Guitare & Claviers, a French magazine.

During the making of the album, Young and his fellow musicians consumed Honey Slides, a concoction of marijuana and honey. To make it, you grind up cheap weed until it’s fine, put it in a frying pan, heat it until it starts to smoke, and remove it from the flame. Heat honey in a separate pan until it’s slippery, then combine the two and eat it by the spoonful.

I’ve made honey slides, but it had nothing like the effect described in Shakey.

“The high was debilitating. 'People passed out,' said Elliot Roberts. 'This stuff was, like, way worse than heroin. Much heavier. Rusty [Kershaw] would pour it down your throat and within ten minutes you were catatonic."

After recording On The Beach, Young made another album, Homegrown, an album that went unreleased for 45 years. At a listening party for Homegrown, Young played Tonight’s The Night, which was on the same feel. At the encouragement of Rick Danko, Young released the final part of The Ditch Trilogy. He felt the performances on it were stronger than Homegrown, which he described as a “very down album.” The songs were very personal and concerned his deteriorating relationship with actress Carrie Snodgress, which may explain his reticence.

“I apologize. This album Homegrown should have been there for you a couple of years after Harvest,” Neil Young said. “It’s the sad side of a love affair. The damage done. The heartache. I just couldn’t listen to it. I wanted to move on. So I kept it to myself, hidden away in the vault, on the shelf, in the back of my mind... but I should have shared it. It’s actually beautiful. That’s why I made it in the first place. Sometimes life hurts. You know what I mean. This is the one that got away.”

The rawness, pain, and beauty are what keep drawing me back to the Ditch Trilogy. My initial Neil Young obsession kicked off in 2009 and ever the fan of lost albums, I tried to find Homegrown bootlegs with little success, but found a high quality rip of Time Fades Away.

When my paternal grandfather died shortly before Thanksgiving in 2010, I was with some friends; we were going to see a movie that night. We’d stopped for dinner at White Castle. The last song I heard before finding out my grandfather had died was “Bela Lugosi’s Dead.”

I got a phone call from the man who would end up murdering my mother nine years later. All I could think of at the time was, “'Cause people let me tell you/It sent a chill up and down my spine/When I picked up the telephone/And heard that he'd died out on the mainline.”

I turned to Neil Young because he was the only one I could think of who could understand my grief and how it tore me apart. Losing my grandfather was like losing my father. He had filled that role after his son decided not to be a part of my life anymore.

I was a senior in college, and this only added to the despair I felt. My future felt bleak. I had no prospects for after school and had nothing really to show for my time in college. When I thought about killing myself, I listened to Tonight’s The Night and wallowed in the sorrow of a stranger instead. It got really bad my final semester when I developed a painful ulcer that left me in agony a lot of the time and impacted my ability to attend class and generally enjoy life. The Ditch Trilogy was a life preserver.

I saw Young perform a solo acoustic show in Chicago the day I graduated college, drove straight from the ceremony. A fitting finale to a year of struggle that I survived thanks to him.

I interviewed Poncho Sampedro about a year later, and while he joined Crazy Horse after the Ditch Trilogy, I made a point to tell him just how important those albums were and Neil's impact on me. He could tell I was such a fan that he gave me 33 minutes instead of 20. I also like to think he told Neil what his music had done for me. I imagine that would have made him happy, that while he couldn’t save Danny or Kurt, someone else found a way through because of him.

Hey, this was beautiful, thank you for sharing it. I teared up a bit in the bathtub reading and listening to Sleeps With Angels.