Talk About The Passion

I had wanted to write about R.E.M. soon; I figured I should since I’d already written about The Replacements and Hüsker Dü, two members of my Holy Trinity of 80s alternative rock. This week was perfect for it after a few recent events. I saw a clip of them from 2004 playing “Born To Run,” talking with The Boss, and rehearsing for a show.

Then, all four original members reunited to perform at their Songwriters Hall Of Fame Induction. The last time all four had played together was in 2007 at their induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame

And then I became aware of one person on Twitter who not only doesn’t care for R.E.M. but thinks “Nightswimming” is an awful song—not merely bad but the worst of all time.

Perhaps it’s a bit of engagement bait, he prefers Sublime, which makes engaging with him pointless. Clearly, we value very different things in music. I’m no fan of Sublime, but they certainly have their place, who am I to look down on the taste of others? He’s also a New York Knicks fan, so we are clearly diametrically opposed. He was not happy with how round eight of Hicks vs. Knicks turned out, believe you me!

I can imagine finding R.E.M. boring, at least during their Warner years, which tend to be more low-key than their IRS days. Their slower songs are probably the ones people remember, the songs that seemed inescapable on MTV and the radio. Or maybe they were annoyed by “Shiny Happy People.” There are some exceptions, of course, but they’re not quite as punchy as “Radio Free Europe.”

I prefer the jangly stuff. Which is why Reckoning is my favorite album of theirs. Ten variations on jangle. And much like Pavement, “Time After Time” was my least favorite song. Listening to it again made me like it more than in the past. And I’d say I like every track on their sophomore album.

A dream I had when I was younger was singing “(Don’t Go Back To) Rockville” at karaoke. It’s one of my favorite songs on the album, which doesn’t always translate to a good karaoke choice, but the country aspect of it makes it good for my vocal range, and generally, country never fails for me as a karaoke choice.

Plus, I love the fourth verse. It’s enough of a change from the rest of the song that you could make an argument for that as the bridge.

I fulfilled that dream at a barcade I used to go to in Bismarck. In that same location, I won a night of trivia by myself; music was the focus, and I had a string of perfect answers that powered me to the top, including a round where I didn’t miss a question. I think I went about 15 questions without missing one.

There’s a moment in “Harborcoat” when it gets to the chorus that always makes me think of when a movie is about to start. When the curtain pulls back, the screen shifts to the appropriate size for the film. Most often, the screen gets wider. And that’s what it feels like in Harborcoat, it’s expansive

R.E.M. has also been on my mind because of a discussion with friends visiting from out of town. Knowing I was a Hoosier, one of them asked me for my thoughts on John Cougar Mellencamp. He’s a polarizing musician, so I answered like a politician and praised the production on Scarecrow without revealing my true thoughts on him. The response told me it was okay to be more effusive about The Coug.

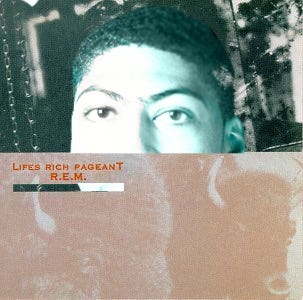

R.E.M. recorded Lifes Rich Pageant at the studio Mellencamp used and with his producer, that was in the back of my mind as we talked about Seymour’s most famous son. We also discussed the new Springsteen live album from the 1984-85 tour.

Something about The Boss allows men to bear their souls to one another or at least be more honest about their emotions. Sports are similar, which may explain the overlap in Springsteen aficionados and sportswriters. Passion is at the heart of his music, it manifests in a number of ways, most often as a desire to escape, to throw off the shackles of one’s hometown.

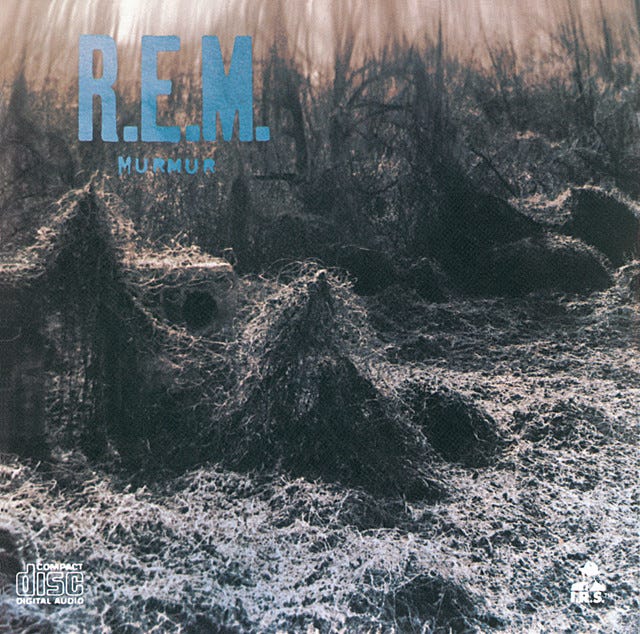

The past haunts Springsteen, but not R.E.M., though there is some hint of the darker aspects of their home; they’re southern boys, after all. They paint a vision of a different South, one with room for eccentrics, oddballs, and others who may fall out of the typical range of stock southern characters. You could argue that they’re like the kudzu on the cover of Murmur, their first album; both represent new iterations of the South, a changing landscape.

Kudzu covers up native plants, can damage infrastructure, and produces ozone. Its roots are edible, its fiber can be used for baskets, and it can be used as animal feed. It can also help with soil erosion and improve the quality of the soil, which is why it was planted across the South in the 1930s and 1940s.

It was first brought to the U.S. for the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia and the World’s Fair in Chicago. The Soil Conservation Service paid $8 an acre to those who planted it. At the peak of its planting, the vines covered over a million acres.

Three members of R.E.M. were born outside of Georgia but moved there by high school.

It was in the college town of Athens the four met. Peter Buck was a record store clerk at Wuxtry Records and met Michael Stipe. The two realized they had a similar taste in music and that Stipe had been buying many of the records Buck had set aside for himself to buy.

They met Mike Mills and Bruce Berry, both students at the University of Georgia. The future rhythm section had played music together in high school.

They agreed to work on songs together and spent months rehearsing in a deconsecrated church that was also the site of their first gig.

They dropped out of college and tried to make a go of it at making music and began touring. An arduous prospect in those days for an independent act, they had to figure out the logistics of it and didn’t make any kind of living, they were each eating on $2 a day.

In April 1981, they recorded a single at Mitch Easter’s studio. He produced their music until 1984 and really helped define their sound. He was a musician himself, in a group called Let’s Active. Musically speaking, they were fellow travelers with R.E.M.

That first single — “Radio Free Europe” — was on the Hib-Tone label. The initial run of 1,000 ran out, and 6,000 more copies were made in a repress.

That October, they recorded Chronic Town, their debut EP, and I.R.S. Records. The EP was released in August the following year.

They recorded their debut album, Murmur, in January and February of 1983. That album was released to critical acclaim but without sales to match. The follow-up, Reckoning, received similar accolades and improved commercial fortunes.

Their next album, Fables of the Reconstruction, was recorded in England with Joe Boyd, who had produced records for Nick Drake, Fairport Convention, Vashti Bunyan, The Incredible String Band, and early Pink Floyd and Soft Machine songs.

The recording process was more taxing than the band anticipated, and they also experienced discomfort due to the cold weather and food during their stay in England. Their follow-up, Lifes Rich Pageant, was recorded at Belmont Mall Studios in Belmont Indiana. While making the album, they spent some time in Bloomington, which was under a half-hour away.

Document was their final album on I.R.S., they signed with Warner Bros. after their contract expired. Warner had a reputation for being an artist friendly label, a rep that goes back to the 60s and 70s and artists like Harry Nilsson, Van Dyke Parks, and Randy Newman. When Hüsker Dü made the leap to the majors, Warner was where they went. And The Replacements signed to Sire, a Warner subsidiary.

The Warner years are when R.E.M. blew up. Green followed in 1988, and Out of Time came out in 1990. It featured their biggest hit, the song everyone knows: “Losing My Religion.”

It was a hint of things to come. Their follow-up, Automatic for the People, was originally intended to return to more guitar-oriented and uptempo tracks. Instead it was more somber and lyrically it focused on grief, loss and change.

Monster followed in 1994, essentially a glam rock record that also showed off the influence of grunge, and New Adventures in Hi-Fi, an album inspired by Time Fades Away. The band recorded tracks during and after the tour.

It was their last album with Bill Berry. During their 1995 tour, he suffered an aneurysm and two years later decided to pursue a life as a farmer. The group continued on as a trio and released five more albums that fulfilled their second contract with Warner: Up (1998), Reveal (2001), Around the Sun (2004), Accelerate (2008) , and Collapse into Now (2011)

They called it quits on September 21, 2011. One of the quotes in the press release has stayed with me, “A wise man once said–‘the skill in attending a party is knowing when it’s time to leave.’” Wise words. Leave them laughing when you go. Don’t give yourself away. That’s something I consider often. There comes a point where you know it’s for the best if you bow out.

They also released a compilation that I spent much time listening to that fall, during my first year of grad school and living in Brooklyn: Part Lies, Part Heart, Part Truth, Part Garbage 1982-2011.

While driving friends around one time, “The One I Love” came on, and I sang along, taking the Mike Mills part.

Everyone notices Peter Buck, hard not to, his arpeggiated playing in their early days when they were jangling like The Byrds is his signature sound. But Mike Mills was the group’s secret weapon musically, providing melodic bass lines that hinted at their post-punk influences and great backing vocals, an element of their songs that often pushed them from good to great. In basketball terms, he’s what you’d call a glue guy.

One of my friends praised my singing and said I’d be good at backing vocals. I’d always liked that song anyway because it sounded like Neil Young’s “My My, Hey Hey (Out of the Blue” and “Hey Hey, My My (Into the Black),” the songs that open and close Rust Never Sleeps. They were also the songs that Kurt Cobain quoted in his suicide note.

Cobain was an admirer of R.E.M., a mutual feeling; Stipe served as Godfather to Cobain and Courtney Love’s daughter, Francis Bean Cobain.

Stipe planned a collaboration with Cobain to help save his life; like many of his friends, he had concerns about the Nirvana singer’s mental state and drug use. It never came to be, though Stipe honored him with “Let Me In” on Monster.

My earliest memory of R.E.M. is laying in the top bunk in the room I shared with my younger brother in our townhouse and listening to my clock radio.

Memory fails as to the exact circumstances that brought me there. I might have been grounded and not allowed to watch television, maybe I was tired or just sick.

It was sometime late in 1999 or early 2000, around the time of the release of Miloš Forman’s Man On The Moon, his biopic of the late comedian Andy Kaufman. The title for the film came from the R.E.M. song on Automatic for the People about Kaufman.

I was aware of the film; I’d seen behind-the-scenes footage on HBO or somewhere similar. I was vaguely aware of their involvement on the soundtrack. I think I knew of them because of “Losing My Religion,” “It’s The End of The World As We Know It (And I Feel Fine),” or “Everybody Hurts.”

But it was “The Great Beyond” that pulled me in. Around that time, I was watching Vh1 in an effort to relate better to my classmates. I remember seeing the music video on there and liking it and the music.

Musically, it feels like a companion piece to “Man On The Moon,” like its fraternal twin. Akin to “Like A Rolling Stone” and “Positively 4th Street”

I came to associate it with my grandfather's passing, though that may have come later when I listened to Part Lies, Part Heart, Part Truth, Part Garbage 1982-2011. It was released in November, roughly a year after my grandfather had died. Even a year on, I missed him terribly.

He had been like a father to me. I think the line “There’s a new planet in the solar system” made the connection along with the song’s title that portended the afterlife. It was nice to think that my grandfather had returned to Stardust, that the cycle of life had moved from death to rebirth, and that his existence continued in a different way.

The association might also have been due to listening to Automatic for the People after he died. In that period, I turned to music for comfort, mostly Neil Young’s Ditch Trilogy. But I also listened to the blues, “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” by Blind Willie Johnson, one of the pieces featured on the Golden Disc of the Voyager spacecraft, and David Bowie’s cover of “Across the Universe” were also in heavy rotation.

My grief continued beyond the fall semester and into the spring semester. Stress from a photojournalism class, as well as medication from wisdom teeth extraction, had burned a hole in my stomach.

The peptic ulcer bothered me most when my stomach was empty, so I ate a lot of fast food, perhaps inspired by Rob Sheffield writing about that in Love Is A Mixtape: Life and Loss, One Song at a Time, while grieving his wife, Renée Crist, who had died of a pulmonary embolism on Mother’s Day 1997. Each chapter of the book is named for a mixtape.

“First song, side two: R.E.M.’s ‘Man On The Moon.’ Did Renée ever make a mix tape without R.E.M.? A whole generation of southern girls raised on the promise of Michael Stipe.” - Rob Sheffield, Rumblefish, Ides O’ March 1993, Love Is A Mixtape: Life and Loss, One Song at a Time

She was a southern girl and loved R.E.M. and that was one of several bands the two bonded over. Music brought them together, made them fall in love, and kept them together.

“She told me you can sing The Beverly Hillbillies theme to the tune of R.E.M.’s ‘Talk About the Passi’ T’’ That was it, basically; as soon as she started to sing ‘Talk About the Clampetts,’ any thought I had of not falling in love with her went down in some serious Towering Inferno flames. It was over. I was over.” - Rob Sheffield, Big Star: For Renée, October 1989, Love Is A Mixtape: Life and Loss, One Song at a Time

”I was hungry all the time. I would drive to Arby’s or Burger King and find a space in the parking lot and eat something hot and salty that would make me feel even hungrier when it was gone.” - Rob Sheffield, Paramount Hotel, June 1997, Love Is A Mixtape: Life and Loss, One Song at a Time

Automatic for the People felt cathartic. The opening track, “Drive,” had lyrical imagery that called to mind The Raft of the Medusa, which I had seen in person at the Louvre in Paris the summer before my grandfather died.

The album helped me grapple with my complex emotions around his death, I found much comfort in it. Even “Everybody Hurts” had become a bit of a punchline by that point because of its use as a too-on-the-nose musical choice for suicide PSAs and similar moments intended to invoke catharsis. I found comfort in it. But the two songs that brought me the most joy were “The Sidewinder Sleeps Tonite” and “Man On The Moon.”

There is a warmth to them that feels like a reassuring hand on the shoulder from a friend. No words spoken, but the look in their eyes and the firmness of their grasp says it all. The type of exchange that can only happen from a real connection, true friendship.

It also calls to mind the conservations that follow a funeral. Anecdotes about the deceased are exchanged; there are laughs, tears, and conversations about big-picture issues. Death has a way of making one reflect on one’s life and remembering the things that really matter like friendship and love. Life is too short and too cruel to live without either of those.

By that point in my life, I had become a convert to R.E.M. I can trace that back to a few moments early in college, the arc was similar to that of Hüsker Dü. “So. Central Rain” was on the listening list for my Rock Music in the 70s and 80s course. The other was the radio station. The last show I did with my co-host was freeform. The DJ before us played “Radio Free Europe.”

My co-host had been assigned by the radio station and it was a pairing that benefited us both. I wasn’t into indie rock much yet the , but he was. He introduced me to The Clientele and many other bands. I think I helped him appreciate some of the dinosaur bands I listened to more. His greatest impact on me was a night near the end of the spring semester of 2009.

He had a VHS copy of The Hidden Fortress he’d rented from the library, but there was no VCR and none available to rent. I had a TV with one built-in, and we watched it in my dorm room. He hooked me up with his MP3 collection and really helped expand my taste in music. I heard more De La Soul because of him. That was the first Akira Kurosawa film I ever saw.

The next semester, I became a music librarian. Nobody ever stopped by the station during my shifts, so I’d go through the stacks and pull out interesting CDs. One of those was And I Feel Fine... The Best of the I.R.S. Years 1982–1987.

That was my real introduction to early R.E.M., and it made me love them. I loved playing those songs in the car with the windows down. I have a vivid memory of listening to a slow version of “Gardening At Night” while driving on the road near my middle school and high school during a summer evening. I always think of warm weather and green grass when I hear those early R.E.M. songs.

So I explored those early indie albums. I’m sure over the course of my radio shows I played most of Chronic Town, Murmur, and Reckoning. A local bar we went to for drinks and indie rock shows had paintings of famous album covers on the walls, one of them was Reckoning.

Because the band members were also music geeks, I was turned on to their contemporaries like The Feelies, Let’s Active, The dB’s, Guadalcanal Diary, Pylon, and many others. I also discovered an obscure 90s band called Lotion in the stacks of the music library.

Thomas Pynchon wrote the liner notes for their second album, Nobody’s Cool. On their self-titled EP was a song called “Gardening Your Wig,” a mashup of “Gardening At Night” and “Flip Your Wig.” R.E.M. and Hüsker Dü: two great flavors that taste great together.

I can go months and maybe years without deliberately listening to R.E.M. every time I return to them, I remember the effect they had on me, and I remember what it is to love music and feel passion for it. Another important piece of life’s rich pageant.