Stove by a whale

A close study of any life reveals common motifs and recurring imagery, enough of them to imbue any personal narrative with a literary quality. At least, that’s how I see it as a veteran writer who specializes in features and profiles.

The logic is sound: humans engage with the world through fiction; it brings order to chaos, and it helps make sense of the world. Your family member being killed wasn’t a meaningless act of violence. Their fate has significance not only for their story but yours. Human nature can be better understood when it can be diagrammed and analyzed. This fatal flaw is what laid him low, those chance encounters are why they were destined to meet and fall in love.

Surely all this is not without meaning. A compelling narrative can help the observer better understand themselves and perhaps save them from their fate with some self-awareness.

Recurring images or motifs aren’t planted in the life of a person by some author; they happen from circumstance, where a person lives, who they know, and what sort of life they lead.

The frequent appearance of birds of prey doesn’t portend some coming disaster; it just means living in a rural setting with a healthy ecosystem.

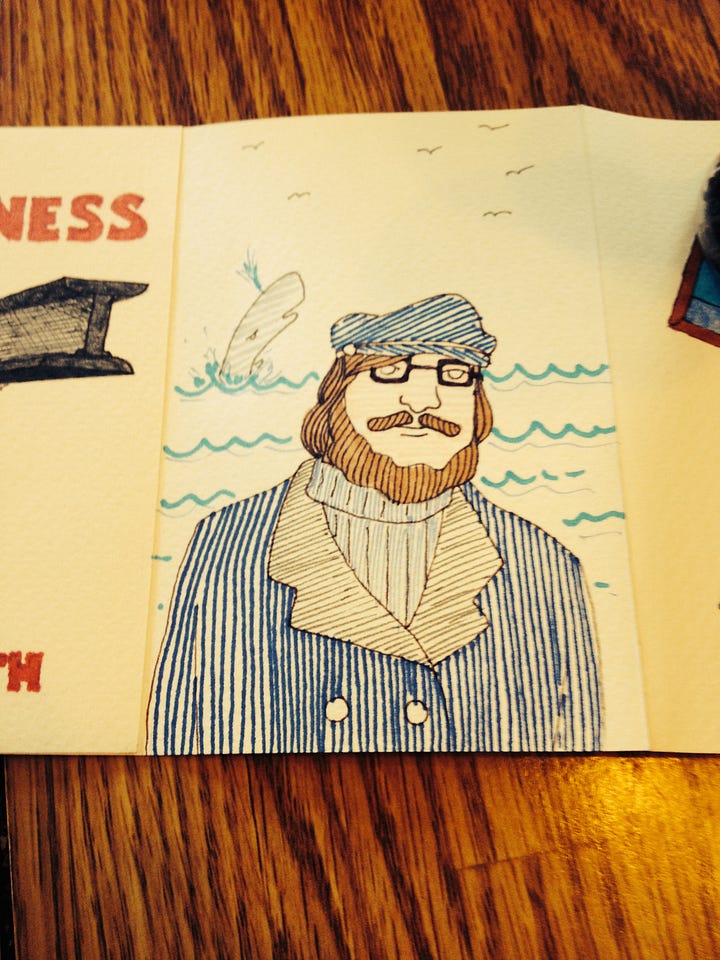

Whales have been a recurring presence in my life for as long as I can remember. SeaWorld and its captive orcas did not have their current stigma. We’d visit the park to see Shamu when in San Diego or Orlando. The plight of one such creature was depicted in Free Willy, a popular film for people my age, and the basis for insults and unkind nicknames for people like me, though not necessarily directed at me.

I’ve spent most of my life fat; whale is a go-to put-down for many people. I leaned into that by getting a Moby-Dick t-shirt and figured I’d beat someone to the punch. Sometimes it comes unintentionally and from a well-meaning place.

In the second grade, during gym class, we played dodgeball or something similar, and I somehow managed to avoid getting knocked out of the game. I was never particularly coordinated, fast, or otherwise gifted athletically, but for whatever reason, that day, I found success.

The gym teacher praised me; he called me elusive, like a humpback whale.

It probably wasn’t the first time I was compared to a whale, but it was the first time in a positive sense. It was a unique way of describing my success in dodgeball; that’s something I’ll always appreciate about that teacher. I didn’t take it as a dig at my weight then, and I doubt that was the teacher’s intention.

I have source amnesia for Moby-Dick. Aspects of the story, like the mad sea captain hellbent on revenge, seem woven into the culture, with the same heft as fables, folk tales, myths, Shakespeare, and the biblical.

The significance is immediately understood when describing something as a white whale.

Even if you’ve not read the book, you understand it on some level because of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan or Star Trek: First Contact, perhaps. If I were to guess where I first encountered Moby-Dick, my guess would be The Pagemaster, which features both Ahab and the whale.

I knew the famous opening of “Call me Ishamel.” (though technically, that honor belongs to “The pale Usher—threadbare in coat, heart, body, and brain; I see him now. He was ever dusting his old lexicons and grammars, with a queer handkerchief, mockingly embellished with all the gay flags of all the known nations of the world. He loved to dust his old grammars; it somehow mildly reminded him of his mortality.”)

A Wishbone adaptation was the first one I ever read. Jaws is like a speed-run of a story. I didn’t actually read the book proper until I was in college. I started and stopped it several times over my first two years. My interest was as fickle as the wind. Sometimes I’d be racing along, bearing down on a final destination.

Finally, I finished it in the summer of 2009. It had met my expectations and more. There’s a perception about canonical art that it’s dry, serious, and boring when nothing could be further from the truth.

It’s queer; very queer. And funny. I can’t help but chuckle at the thought of Peter Coffin messing with Ishmael in his description of Queequeg. Before the apartheid asshole ruined Twitter, one of my favorite accounts to follow was @MobyDickAtSea. Every so often, it would tweet excerpts from the book. Melville’s prose is so good that even stripped of context, it’s pretty compelling stuff. That account has since deleted all its tweets in response to the new ownership.

At the student recreation center, when I’d get on the rowing machine for a workout, I’d imagine myself in a whaling boat, rowing after the white whale.

Apart from that account and watching the John Huston adaptation of the book, one of the television adaptations, I didn’t engage with the text again outside of a failed re-read after Hurricane Sandy hit NYC until five years ago.

I revisited Moby-Dick and other favorites after my mother was murdered. I wanted solace in the familiar. This time around I opted for an audiobook experience. The first one was an adapted version; the fat was trimmed, and the book was turned into a stage play, but I wanted more, so I turned toward the Recorded Books version, and it only deepened my love for my favorite book. Hearing it read aloud made me appreciate the language in the book and the way Melville strung sentences together.

I also found recognition of myself in it. I’ve always had a gloomy sort of disposition and that’s manifested in a few ways. One that comes to mind is telling my mother that I wished I was dead the night before we were to take a trip to Kings Island. I should have been on top of the world, yet I was caught in melancholy.

So Ishmael going to sea to stave off suicidal thoughts resonated with me. I saw a lot of myself in two characters: Ishmael and Ahab. The former because of his sadness but also because he was the one to live to tell the tale. He keeps their memories alive as surely as the chapel in New Bedford does. I was thinking of that recently as a church my mother was involved with named their rose garden in her memory.

“AND I ONLY AM ESCAPED ALONE TO TELL THEE” Job.

I’ve thought a lot about the final lines of the book. I know it’s silly to call myself an orphan given my age and the fact that my dad is alive, but we don’t talk, and the suddenness and violence of my mother’s ending, as well as my proximity to it, made me feel that way.

“On the second day, a sail drew near, nearer, and picked me up at last. It was the devious-cruising Rachel, that in her retracing search after her missing children, only found another orphan.”

Ishmael lived, which is a blessing and curse like “May you live in interesting times.” Ishmael shares the story of the Town-Ho with acquaintances in Lima, and it’s clear he is doing so after the events of the book. He does not seem weighed down by his traumatic experiences, or at least he can bear them. Ahab, his captain, is not so lucky.

Rereading it, it was clear to me that Ahab is suffering from some form of PTSD because of losing his limb. It wasn’t the dismantling that destroyed him, it was living with it. In the five years since my mother was murdered, I’ve only gotten crazier.

“Ahab and anguish lay stretched together in one hammock, rounding in mid winter that dreary, howling Patagonian Cape; then it was, that his torn body and gashed soul bled into one another; and so interfusing, made him mad.”

Ahab was always a compelling character to me and one that became more sympathetic after my own dismasting. There are times he has the opportunity to turn away from his quest for vengeance, such as when the compasses are found to be pointing in the opposite direction of the white whale. Ahab considers giving up the chase to return to his young wife back home. But alas, he feels compelled to see his revenge to the end. Ultimately, it costs him his life and the lives of the crew; only poor Ishmael survives floating on a coffin Queequeg had fashioned when he was convinced he was dying.

Ahab’s behavior seems irrational, but when viewing his actions through the lens of PTSD, it all makes sense: the bouts of rage and self-destructive tendencies are all common behaviors following a traumatic event.

Those living with that diagnosis can recognize it immediately, just as having PTSD makes Slaughterhouse-Five abundantly clear. While I hate the trope both everything being trauma, working under that framework is elucidating. The Lord of the Rings, like Slaughterhouse-Five, is the work of a man who has borne witness to the horrors of will and has been left changed by that experience.

PTSD is a very isolating experience, and living with it is unbearable at times, so Frodo feeling out of place in The Shire after his trials makes perfect sense, as does his physical reaction when he arrives at the anniversaries of his round by knife, fang, and tooth. Some days are harder than others, and if I’m struggling, I can understand why, especially if it’s near a holiday or anniversary. I haven’t celebrated a holiday in five years. I’ll mark the occasion in some way. On Christmas Eve, I go to Red Lobster and see a movie, usually It’s A Wonderful Life. Traditionally, Italian-Americans celebrate Christmas Eve by eating seafood. It’s known as Festa dei Sette Pesci or the Feast of Seven Fishes.

We’d go to Red Lobster because it didn’t make sense to prepare seven dishes when Christmas is also a big cooking day.

I feel very low at the holidays, so the Capra film is a nice mood booster, makes me wonder what a world without me would look like. At times I wish I could have that experience and the Tom Sawyer one of attending my own funeral.

The audiobook of Moby Dick has become a steady companion for long drives, I return to it often. Nearly five years ago, I listened to it on an East Coast road trip that included a stop in New Bedford at the whaling museum. Every year it hosts a reading marathon of the book.

I named that car the Pequod, partly because of my love for the book but also for self-destructive purposes. Naming your car after a doomed whaling vessel seems like tempting fate. Perhaps, like Ahab, I am compelled to be the author of my annihilation.

Five years ago, I broke a record for a year going to pot. If you wanted to be precise, you could pinpoint the moment the murder-suicide happened, roughly 3:30 a.m. I was at home and sleeping when it happened. The medication I was on at the time often led me to waking in the middle of the night, and this night was no different, or so I thought.

I never heard any gunshots, but I’m sure that they may have stirred me out of deep sleep. Or maybe it was the sound of a body hitting the floor above me. My room was in the basement. I picked it because I thought it would be cooler in the summer, and I really wanted to lean into the stereotype of Millennial failsons living at home. I used to live at home, now I stay at the house.

From a practical point of view, it made sense, the newspaper office was less than ten minutes away, and they didn’t pay too well. No reason to pay rent when you can live at home.

His room was also in the basement. Though technically together, by that point, they were functionally roommates.

I’m not sure what caused the events of that day, but I have a rough idea. My mother had decided to end the relationship. She’d met someone new through Words with Friends. I had picked up on it because I’d heard her talking and laughing on the phone. I’m an observant person, and that’s why I do well as a journalist, particularly with features and profiles.

When she spilled the beans on it, she was shocked that I was aware. At the time, I raised concerns about the very thing that happened. He found out about it, and she told him it was over essentially, but they attempted to work things out.

Christmas was a somber occasion that year, there was a foreboding air in the house. In the time leading up to The Incident™️ I locked my door at night. A key to the door was readily available, but I figured that if he wanted to shoot me, he’d make noise trying to get in or would be delayed getting the key.

From what I gather, she had told him that it was over, either at the NYE party they’d attended or on the car ride back. Or maybe in the garage. He went down to the basement and retrieved a pistol, came upstairs, and shot her point blank between the eyes before turning the gun on himself.

When I found him, he was lying on his back, empty unseeing eyes staring at nothing, pink brains seeping out the hole in his skull, I thought of the death of the one-finned whale and another whale killed earlier in the novel

“He’s dead, Mr. Stubb,” said Tashtego.

“Yes; both pipes smoked out!” and withdrawing his own from his mouth, Stubb scattered the dead ashes over the water; and, for a moment, stood thoughtfully eyeing the vast corpse he had made.”

Later on, when my anger at him was at its peak, I thought of butchering him like a whale, as described in the book, unraveling him like an orange.

“He piled upon the whale’s white hump the sum of all the general rage and hate felt by his whole race from Adam down; and then, as if his chest had been a mortar, he burst his hot heart’s shell upon it.”

When I heard the crash, I had assumed that my mother had fallen and might need help getting up. She’d had her hip replaced the previous April and her knee replaced in October. I was going to go upstairs, but something told me to stay put. The crash was pretty loud, like nothing I’d heard before, but I don’t hear too many bodies collapsing lifeless to the floor generally.

I heard my mother’s laughter which made me think she was fine and didn’t need assistance.

“Hark ye yet again,—the little lower layer. All visible objects, man, are but as pasteboard masks. But in each event—in the living act, the undoubted deed—there, some unknown but still reasoning thing puts forth the mouldings of its features from behind the unreasoning mask. If man will strike, strike through the mask! How can the prisoner reach outside except by thrusting through the wall? To me, the white whale is that wall, shoved near to me. Sometimes I think there’s naught beyond. But ’tis enough.”

In a certain light, that’s true. I know now that she was dead by then. Either that body was hers, or it was his. Regardless, she was dead by then. I’ve not been able to understand that. It could be just a product of my traumatized brain, but it’s a mystery that will stay with me and haunt me like one of the phantoms alluded to in the book.

I don’t know what the future has in store for me; life feels incredibly bleak, and I feel like I’m running out of pavement/time, whatever. I’ve felt like a dead man walking for the last five years. Like Phil Ochs died in Chicago in 1968, I died in Martinsville in 2019.

“By Phil's thinking, he had died a long time ago: he had died politically in Chicago in 1968 in the violence of the Democratic National Convention; he had died professionally in Africa a few years later when he had been strangled and felt that he could no longer sing; he had died spiritually when Chile had been overthrown and his friend Victor Jara had been brutally murdered; and, finally, he had died psychologically at the hands of John Train.”— There But for Fortune: The Life of Phil Ochs by Michael Schumacher

I don’t know if I too will ultimately take my life like Ochs did, but I know the odds for that aren’t zero.

Another line I come back to comes from the epilogue.

“The drama’s done. Why then here does any one step forth?- Because one did survive the wreck.”

It gives me strength and want to keep persevering in spite of how bad things are, how much I hurt, and how I am worse off five years removed being stove by a whale.

“I know not all that may be coming, but be it what it will, I’ll go to it laughing. ”