Jude: Doesn't really matter, you know, what kind of nasty names people invent for the music. But, uh, folk music is just a word, you know, that I can't use anymore. What I'm talking about is traditional music, right, which is to say it's mathematical music, it's based on hexagons. But all these songs about, you know, roses growing out of people's brains and lovers who are really geese and swans are turning into angels - I mean, you know, they're not going to die. They're not folk music songs. They're political songs. They're already dead. You'd think that these traditional music people would - would gather that mystery, you know, is a traditional fact, you know, seeing as they're all so full of mystery.

Keenan Jones: And contradictions.

Jude: Yeah, contradictions.

Keenan Jones: And chaos.

Jude: Yes, it's chaos, clocks, and watermelons - you know, it's - it's everything. These people actually think I have some kind of, uh... fantastic imagination. It gets very, uh, lonesome. But traditional music is just, uh... it's too unreal to die. It doesn't need to be protected. You know, I mean, in that music is the only true valid death you can feel today, you know, off a record player. But like everything else in great demand, people try to own it. Has to do with, like, uh, the purity thing. I think its meaninglessness is holy. Everybody knows I'm not a folk singer.

From I’m Not There (2007) directed by Todd Haynes

What is folk music, and what is not folk music? Seems like one of those cop out, bullshit questions designed to let you slip out of a challenging conversation and dodge the subject altogether. But it’s one worth asking when considering the folk process: how songs and stories are passed on. The songs of childhood had authors, and some of them may still be under copyright, while the origin of others remains unknown or unthought of currently.

Children sing “London Bridge Is Falling Down” without having an idea about its meaning or its origins. That’s a fact of life. In any language, you’re bound to come across turns of phrase or idioms that are so ubiquitous and understood that you never bother to think of their origin.

It’s so woven into the fabric of your life that through usage and context, you’ve intuited its meaning.

Children don’t need to know about songs’ origins to appreciate them. Though in the case of this one, there are many possible meanings of the song.

The song goes back centuries and may have origins in other bridge-related rhymes from other countries.

One school of thought suggests the song is a reference to an attack by Vikings in the 11th century that led to the destruction of the bridge. Another is more grim; British folklorist Alice Bertha Gomme suggested that it was related to child sacrifice/immurement.

In folklore, there is a tradition in several cultures around the world of sacrificing someone to ensure the sturdiness of a structure.

The one I was most familiar with was that it referred to the Old London Bridge, a structure that was built in the 13th century and was in use until it was replaced in the 19th century.

During those long years of service, the bridge featured multiple homes and was crucial to stopping The Great London Fire of 1666. The fire of 1633 had a devastating impact on the bridge, but this time around, the bridge saved more of the city from feeling the heat of the flames. Though the bridge was badly damaged, but due to a firebreak was created on the bridge due to the space between buildings. More of the city would have burned if that were the case.

That bridge was replaced by a new construction in 1831 and was in operation until 1967, when it was replaced by a modern construction that opened in 1973. The old bridge was taken apart and shipped to the United States, where it was reconstructed in Lake Havasu, Arizona. The bridge opened in 1971.

One purpose of that song is for a game. That’s the function of many songs geared towards children. In a time before mass media, songs filled many roles in daily life. Some were used to ease the burden of work, by helping to find rhythm in your toil or to otherwise take your mind to other places.

Some songs were used for entertainment, whether in evenings at home or in social settings. Some songs you sang while you cooked to make the experience more enjoyable and to engage you more deeply with the task at hand. Some songs are sung to help children settle into sleep and contain lyrics they are too young to understand, but express something about the difficulties of parenting.

One of the first folk songs I can recall hearing, beyond the childhood staples, is “This Land Is Your Land,” in a music class in second grade. It did not contain the fourth verse, though the version Guthrie recorded in 1944 with that verse was lost and not found until 1997, after my music textbook had been printed. That verse goes “There was a big high wall there that tried to stop me./The sign was painted, said ‘Private Property.’/But on the backside, it didn’t say nothing./This land was made for you and me.”

A sixth verse was never recorded and contained these lines, which further illustrated the contradictions at the heart of the American experience. “One bright sunny morning in the shadow of the steeple,/by the relief office I saw my people./As they stood hungry,/I stood there wondering if God blessed America for me.”

It calls to mind a famous photograph that appeared in the February 1937 edition of Life, which juxtaposed the prosperity of a white American family with the reality of non-white Americans. Most mistake it for an unemployment line; in reality, it depicts people impacted by the flooding of the Ohio River and was taken in Louisville, Kentucky. The flooding killed almost 400 people, and millions more were displaced by it. One can’t help but think of the people impacted by the flooding in Texas, the wildfires in California, or the many others who have been left holding the bag when a natural disaster occurs.

Along with not knowing of those extra verses, I knew nothing about Woody Guthrie then. I knew he was a folk singer and had origins in The Great Depression, but that’s about it. They certainly didn’t talk about his radical politics or the message that his guitar bore, “This Machine Kills Fascists.” Not that we were delving too deeply into the biography and politics of the music we learned then. One can’t help but think of this Lenin.

“During the lifetime of great revolutionaries, the oppressing classes constantly hounded them, received their theories with the most savage malice, the most furious hatred and the most unscrupulous campaigns of lies and slander. After their death, attempts are made to convert them into harmless icons, to canonize them, so to say, and to hallow their names to a certain extent for the ‘consolation’ of the oppressed classes and with the object of duping the latter, while at the same time robbing the revolutionary theory of its substance, blunting its revolutionary edge and vulgarizing it.”—V.I. Lenin, The State and Revolution

It wasn’t until college and grad school, especially, that I came to know more about Guthrie’s upbringing and politics.

Brooklyn College hosted a conference in 2012 in honor of the centennial of Guthrie’s birth. He entered the world on July 14, 1912, in Okemah, Oklahoma, and was named Woodrow Wilson Guthrie in honor of the 1912 Democratic candidate for President of the United States. As part of the conference, I took a course on Guthrie, Bob Dylan, and other folk music. One of our texts for the class was Woody Guthrie, American Radical by Will Kaufman.

“As he once claimed: ‘If you call me a Communist, I am very proud because it takes a wise and hard-working person to be a Communist’ (quoted in Klein, p. 303). Klein also writes that Guthrie applied to join the Communist Party, but his application was turned down. In later years, he'd say, ‘I'm not a Communist, but I've been in the red all my life.’ He took great delight in proclaiming his hopes for a communist victory in the Korean War and more than once expressed his admiration for Stalin. Unlike his musical protégé, Pete Seeger, Guthrie never offered any regret for his Stalinism,” Kaufman wrote in, Woody Guthrie's “Union War,” a scholarly article published in 2010 for the Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies, Vol. 16, No. 1/2, The Uses of Narrative: A Special Double Issue in Honor of Professor Zoltán Abádi-Nagy (Spring-Fall, 2010), pp. 109-124.

In undergrad, I learned the source of the melody of “This Land Is Your Land,” a song by The Carter Family, “When The World’s On Fire.” Part of my musical education then was becoming aware of how much musical borrowing there was, from phrases, progressions to melodies, music was a living, breathing thing, always in conversation with itself. During one class on the history of rock and roll, my professor played a clip from an episode of the documentary, Folk America, that discussed Guthrie and The Carter Family and how one of their songs impacted Guthrie.

”A fiery young drifter took this traditional hymn tune and transformed it into what would become America’s alternative national anthem. The Carter Family promised justice in the world to come, but Woody Guthrie wasn’t willing to wait. He wrote this on his way across an America devastated after ten years of depression. He was headed for New York City, fast becoming the Mecca of the folk world.”

More on The Carter Family later in this article, they have much to do with the world of folk music, both in their time and after. One of the biggest advocates of Bob Dylan was Johnny Cash, who was married to June Carter, whose mother was Maybelle Carter and whose aunt and uncle were Sara and A.P. Carter.

Guthrie grew sick of hearing Kate Smith sing the Irving Berlin-penned “God Bless America” on the radio all the time. Originally, he called it “God Blessed America for me,” which appears in that final, unrecorded verse. Decades later, another Woody Guthrie acolyte, Phil Ochs, would take a stab at a similarly minded song, “Power and the Glory,” that owed more than a little debt to Guthrie.

Like the Guthrie tune, Ochs’ song recounts some of the natural wonders of America while also being critical of the country for its failure to live up to its highest aspirations, a verse deleted from the recording and found on a demo contained a call to action, “Yet our land is still troubled by men who have to hate/They twist away our freedom and they twist away our fate/Fear is their weapon and treason is their cry./We can stop them if we try.”

Anita Bryant, who had staunch right-wing politics, covered the song, which amused the left-wing Ochs greatly. Not the first time or the last time someone misinterpreted the politics of a song.

Like Dylan, Ochs visited Guthrie when he was in the hospital, and that inspired his tribute, “Bound for Glory,” which contained references to “This Land Is Your Land,” “Pastures of Plenty,” and the song itself was named after Guthrie’s autobiography. “Now they sing out his praises on every distant shore/ But so few remember what he was fightin' for/Oh why sing the songs and forget about the aim/He wrote them for a reason, why not sing them for the same?”

Ochs was a strong believer in the power of music to change the world, “One good song with a message can bring a point more deeply to more people than a thousand rallies,” he was quoted as saying in a 1962 issue of Broadside magazine.

Guthrie had something similar to say in a radio broadcast the year “This Land Is Your Land” was recorded.

“I hate a song that makes you think that you are not any good. I hate a song that makes you think that you are just born to lose. Bound to lose. No good to nobody. No good for nothing. Because you are too old or too young or too fat or too slim too ugly or too this or too that. Songs that run you down or poke fun at you on account of your bad luck or hard traveling. I am out to fight those songs to my very last breath of air and my last drop of blood. I am out to sing songs that will prove to you that this is your world and that if it's hit you pretty hard and knocked you for a dozen loops, no matter what color, what size you are, how you are built, I am out to sing the songs that make you take pride in yourself and in your work,” said Guthrie on a Dec. 3, 1944 radio show.

Divorced from our musical past, we feel unmoored from our identity and what came before and what comes after. Perhaps that’s a factor of modernity. We sacrifice the communal experience for the convenient one. Singing in public was once much more common. At the movies, you would sing popular songs of the day as part of the program. Before the invention of recorded music or radio, sheet music and pianos at home filled the need for music.

About the only place most Americans sing anymore is during the seventh-inning stretch at the ballgame. Music is more accessible than ever, and perhaps that has devalued it, rendered it just another form of content. To be used and discarded as quickly as possible.

It’s less about connecting with the music and enjoying the experience than ticking it off on your list, seeing where it falls at the end of the year in your recap. There is so much to take in that you are paralyzed by choice, and the dopamine receptors of our brain are fried from too much pleasure.

In the film Sinners, music is literally used to connect with the present with the past and future. Samuel “Sammie” Moore (Miles Caton) is the talented 17-year-old cousin of the Smokestack twins (Michael B. Jordan in a dual role) performs at the opening night of their juke joint and his performance is so good, spirits from the past and future join the merrymaking, including spirits from the past of Grace (Li Jun Li) and Bo (Yao), a Chinese coupe who run a local store.

It’s a highlight of a great film that I found fascinating because of my interest in the blues, folk, and country music. Sammie’s performance serves to bring the community together, in the cause of having fun despite the tough times. It’s the middle of the depression, and the Ku Klux Klan and others who uphold Jim Crow laws and customs lurk in the background.

Music is a communal act, which is a big part of folk music. To attend a folk music performance is not a passive act; one is called upon to engage, whether through singing or dancing, or otherwise. Music is not meant to serve as mere background noise.

Much has been written and discussed about Pete Seeger’s objections to Bob Dylan’s electric set at Newport, and I suspect it was related to the quality of the sound and its volume. Too loud and unintelligible for the audience to engage with the music. They received it passively, the way someone seated on a couch engages with the television. It was a commodity, something that could be bought and sold or used to incentivize the buying and selling of goods.

Folk music is, of course, a major touchstone for Dylan, and going through his back pages, it’s easy to find all the allusions he makes to the music of old, weird America.

Along with covering several songs from blues, folk, and country traditions, the Harry Smith-curated Anthology of American Folk Music is a foundational source for Dylan, whether it’s the act of repurposing lines as with “I Wish I Was A Mole In The Ground” by Bascom Lamar Lunsford. In “Stuck Inside of Mobile With the Memphis Blues Again,” the lines, “Mona tried to tell me/To stay away from the train line/She said that all the railroad men/Just drink up your blood like wine,” are a sort of reworking of these lines from the Lunsford song, “Cause a railroad man they'll kill you when he can/And drink up your blood like wine.”

“Down On Penny’s Farm“ is the basis for at least two Dylan compositions: “Hard Times In New York Town” and “Maggie’s Farm.” The latter was played at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival and was the song that sparked a strong response from Pete Seeger.

In the 2005 Martin Scorsese documentary, No Direction Home, Seeger had this to say about the incident and stories about him wanting to use an axe to cut the sound.

“There are reports of me being anti-him going electric at the '65 Newport Folk festival, but that's wrong. I was the MC that night. He was singing 'Maggie's Farm' and you couldn't understand a word because the mic was distorting his voice. I ran to the mixing desk and said, 'Fix the sound, it's terrible!' The guy said, 'No, this is what the young people want.' And I did say that if I had an axe, I'd cut the cable! But I wanted to hear the words. I didn't mind him going electric.”

“Nettie Moore,” a more recent song from his catalog, is filled with allusions, from quoting classic blues songs like Robert Johnson’s “Hellhound On My Trail” and Charley Patton’s “Greenwood River Blues” to lyrics that allude to or directly quote classic folk songs like “Moonshiner,” “Frankie and Albert,” and the original “Nettie Moore.”

Dylan turns the line from the Robert Johnson song, “Blues fallin' down like hail,” to “Blues this morning falling down like hail.” And with the Charley Patton song, it adds another layer of allusion. The line in “Green River Blues” is “I'm goin' where the Southern cross the Dog,” and in “Nettie Moore,” that becomes “I'm going where the Southern crosses the Yellow Dog.” That change is a nod to W. C. Handy. He wasn’t the first to play the blues, but one of the first to publish music that used the form of the blues.

As a child, he developed an interest in music and purchased a guitar without getting permission. Handy had worked and saved for the instrument by selling nuts and berries and soap he made. His father was a pastor and thought that instruments were tools of the devil. “What possessed you to bring a sinful thing like that into our Christian home?" is what his father said, according to Handy’s 1941 autobiography, Father of the Blues.

In Sinners, Sammie faces a similar ethical quandary as he is the son of a preacher but yearns to become a blues man. His father warns him of the supernatural aspect of the blues.

Not unheard of, one of the major tensions for a lot of blues musicians was that they were playing the devil’s music, because the songs dealt with the failings of the flesh instead of spiritual matters.

And the nature of the music itself associates it with the devil, because of its dissonance. The 3rd, 5th, and 7th scale degrees of a major or minor scale are flattened in the blues. In tonal music theory, this creates a sense of tension due to the harsh, sometimes jarring timbre of the sound.

In Western music, there has long been a negative connotation associated with dissonance in music. The tritone, a musical interval of three adjacent whole tones, is sometimes referred to as diabolus in musica - the devil in music - for its connotations with Satan and evil. The title track of the self-titled debut of Black Sabbath makes use of the tritone in the main riff.

Handy’s father arranged for organ lessons, and though he didn’t take them long, his musical interest remained, and he joined a band in secret where he played cornet. He was religious, and the music of the church was a major influence on his future compositions, as was the sound of the natural world.

He worked many odd jobs, and at one job, shoveling fuel into a furnace, he learned how to make music with his coworkers. They used their shovels to tap out complex rhythms and perform a song to ease the tediousness of their task.

“Southern Negroes sang about everything....They accompany themselves on anything from which they can extract a musical sound or rhythmical effect,” he wrote in Father of the Blues.

In that, Handy saw foundational elements for what became the blues.

Handy was trained to become a teacher but left the profession after learning of its low pay and worked at a pipe works plant and played music on the side. He toured with a few bands and then taught music at the school he initially turned down due to low pay. He traveled in Mississippi and encountered a wide variety of musicians and musical styles. His memory was so excellent, he was able to recall and transcribe the music he heard, and was meticulous about keeping records of the sources of the songs.

In 1903, while waiting for a train in Tutwiler, Mississippi, presumably on his way to Clarksdale, where he led an orchestra from 1903 to 1905, Handy encountered a man and wrote about the experience in his book.

“A lean, loose-jointed Negro had commenced plunking a guitar beside me while I slept. His clothes were rags; his feet peeped out of his shoes. His face had on it some of the sadness of the ages. As he played, he pressed a knife on the strings of a guitar in a manner popularized by Hawaiian guitarists who used steel bars. The effect was unforgettable. His song, too, struck me instantly. ‘Goin’ where the Southern cross’ the Dog.’ The singer repeated the line three times, accompanying himself on the guitar with the weirdest music I ever heard.” The song referred to the crossing of the Southern and Yazoo & Mississippi Valley railroads in Moorhead, forty-two miles to the south; the Y&MV (sometimes called the Yazoo Delta or Y.D.) was nicknamed the “Dog,” or “Yellow Dog.”

Tutwiler is one of several towns that can lay claim to the title of birthplace of the blues.

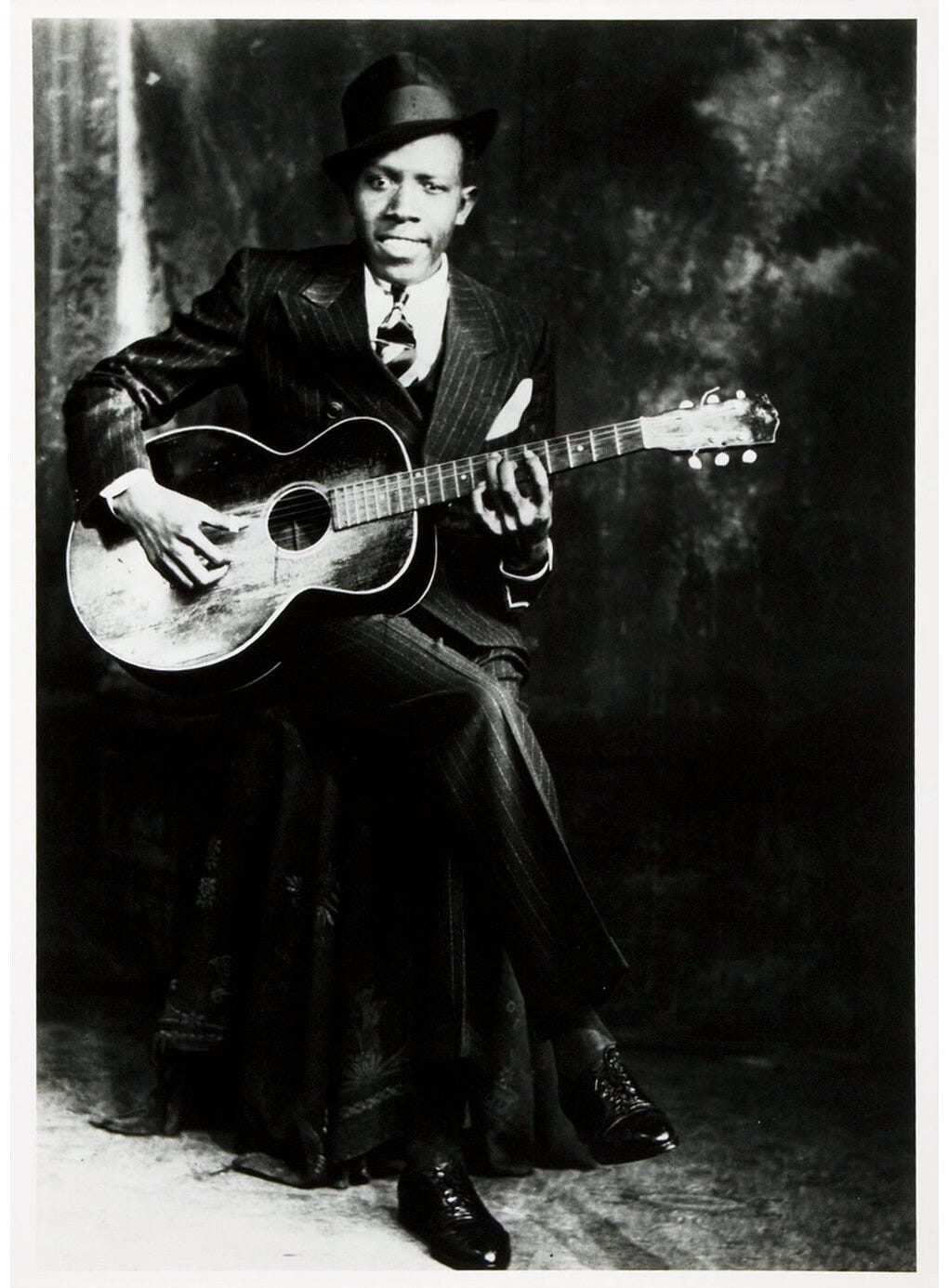

Clarksdale, Mississippi, is another place with plenty of claim to that title due to the number of blues musicians born there or who dwelt there, including Robert Johnson, John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, Frank Stokes, Gus Cannon, W.C. Handy, and Son House.

Clarksdale contains several points of interest in blues history and several markers on The Mississippi Blues Trail, and is home to the Delta Blues Museum, which is housed in the building that formerly served as the passenger depot for the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley Passenger Depot.

Because of its deep ties to the blues, it is the setting for Sinners. There has always been something supernatural about the blues. As previously discussed, it’s a music that trades in worldly concerns, the temptations and sufferings of the flesh, and aspects of it can sound harsh and jarring. Sinister and satanic.

There’s a popular story about Robert Johnson’s gifts with the guitar arising from a deal with the devil. No doubt that’s related to his improvement as a musician. Son House remembered Johnson as a little boy who was a fairly decent harmonica player but lacked skill as a guitarist. He disappeared for a while, and suddenly, he had chops and could really play the guitar.

“Myths are marvelous things, the keys to understanding a culture. For forty years, white folks have had this myth about Robert Johnson selling his soul to the Devil, and that says a great deal about white fantasies of blackness and its links to mysterious, sexy, forbidden powers. Back in 1936, black folks in the Delta had a different blues myth. It was that any guy who got good enough on guitar and learned how to play the latest hip sounds could get the hell out of the cotton fields and make enough money to move to Chicago, wear sharp new suits, and drive a Terraplane,” said ethnomusicologist Elijah Wald, in a 2002 PBS interview.

That was how rumors of him selling his soul to the devil at the crossroads came about. No doubt helped by songs like “Hellhound On My Trail” and “Crossroads.”

Hellfire and damnation are a common thread in blues music because it involves playing a music that is not of the lord, and the image of hellhounds harrying heretics was common in the South.

“Crossroads” is more straightforward in explanation; a crossroad is where a hitchhiker would want to wait to increase the chances of securing a ride. The narrator in that song is in search of one because when the sun sets, there are certain places where a Black man would not be welcome. Sun down towns still very much exist, and non-white people exercised caution when traveling because of that.

A crossroad has a folkloric meaning, as a place where someone could strike a Faustian bargain, and Robert Johnson gets conflated with that due to Tommy Johnson, an earlier blues musician who claimed he sold his soul to the devil in exchange for his guitar skills.

And such a deal goes back further than that; the violinist Niccolò Paganini was said to have made a similar deal to become an extraordinary violinist. It’s an amusing conceit and adds some drama and intrigue to musicians, but it does a disservice to their talent and hard work to reach those levels.

When Johnson went away, he learned how to play like Son House and learned the styles of other guitarists like Isaiah “Ike Zimmerman, who served as his main guitar teacher. Zimmerman himself was rumored to have developed his talents supernaturally by visiting graveyards at night.

In all likelihood, that was just a practical location to play, no deal with the Devil needed. Zimmerman had a wife and kids, and there wouldn’t be anybody to disturb while playing. He gave Johnson guitar lessons there. Decades later, the Allman Brothers would rehearse in a graveyard, and several tombstones there inspired some of their songs, like “Little Martha” and “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed.”

The supernatural appears in Sinners in several forms: the previously mentioned spirits of the past and future that appear during Sammie’s performance, the character of Annie (Wunmi Mosaku) who practices Hoodoo and has a deep knowledge of the supernatural, which comes in handy when Irish vampire Remmick and his two thralls - members of the Klan - visit the Jules joint.

Sammie’s performance attracts the vampires, along with their need to feed. They try to gain entrance with music and money, but they are hesitant to let them in, because the last thing the patrons need to worry about is the white townspeople coming to punish them for the sin of race-mixing.

To demonstrate good intent, the trio of whites performs “Pick Poor Robin Clean,” a blues song. Their performance is fine, precise, and clean in the way of groups like The Kingston Trio during the folk revival of the 1950s.

They later perform “Will Ye Go, Lassie Go?” a song also known as “Wild Mountain Thyme” and a traditional Scottish/Irish folk song, which reads as more authentic than their earlier performance.

Stack’s ex-girlfriend, the white-passing Mary (Hailee Steinfeld), decides to speak to Remnick after the twins realize the juke joint will never turn a profit as their customers can only pay in company scrip and will need other revenue sources. She is turned into a vampire, and when invited back in, she fatally attacks Stack. Mary is shot and flees outside, and they soon realize just the sort of danger they are all in, thanks to Annie’s knowledge.

As the patrons of the joint leave, they are attacked and turned to vampires, and Remmick offers the rest a way out: give up Sammie, and they will spare them. Remmick, a vampire from Ireland, wants Sammie because his musical prowess would allow him to connect to the community he lost. He sings “The Rocky Road To Dublin,” and the rest of the vampires dance a jig in a circle.

When Remmick turns someone, he gains access to their memories and talents. He warns the survivors that the man who sold the twins the building is the head of the local Klan, and they plan to kill anyone still there at sunrise.

As a last bid to gain entrance, he hints at killing Grace’s daughter and the rest of the community. She invites them in, and they fight the vampires. The survivors are able to defeat Remmick and those he turned when the sun rises and burns them up as they flee the now-burning building. As Remmick said, the Klansmen show up and, after sending Sammie home, Smoke kills them all, while also being mortally wounded.

Sammie goes to Chicago and becomes a successful blues musician, and years later, Sammie (now played by Buddy Guy) is visited by Stack and Mary, who offer him a shot at immortality, which he declines. They reminisce about that night, which they think of as the greatest of their lives, at least until the violence broke out.

It would be easy to view vampirism as an allegory for the appropriation of Black music by white record labels and white musicians, but it’s a little more complicated than that. There was a lot of cross-pollination between what became country music and what became the blues.

Black musicians performed folk songs that had their origins in England, Scotland, and Ireland, and white musicians played music on instruments that were African in origin, such as the banjo. They are so interconnected, it’s hard to separate them from one another, so crucial are they to their development. Roots music is the music of the poor, whether in Appalachia, the Deep South, or elsewhere.

“I’m obsessed with Irish folk music, my kids are obsessed with it, my first name is Irish. I think it’s not known how much crossover there is between African American culture and Irish culture, and how much that stuff is loved in our community,” said director Ryan Coogler in an interview with IndieWire.

Remmick is unique for the setting because he is a white man in Mississippi in 1929 without the beliefs of the typical white man living then. Some of that is his background as an Irishman and his age. He offers the juke joint patrons and proprietors a chance at immortality in a community that lacks the hang-ups of the community in which they currently dwell. They need not fear being killed for their skin color.

“It was very important that our master vampire [in] this movie was unique as the situation. It was important to me that he was old, but also that he came from a time that pre-existed these racial definitions that existed in this place that he showed up in,” Coogler said in that same interview.

They just have to give up ever being able to see the sun again and to survive by feeding on others. And while the collective shares their memories, they retain their personalities.

“[Remmick] would be extremely odd, and [the racial dynamics of 1932 Mississippi] would all seem odd to him, but he would see it for what it was and offer a sweet deal, and that the music was just as beautiful,” said Coogler.

A month after the movie came out, there was a moment during the American Music Awards where the singer Shabooezy was puzzled by and laughed at something his co-presenter Megan Moroney read on the teleprompter, about The Carter Family “basically inventing country music.” He was right to laugh, because the truth about country music is more complicated than that. It has many fathers and many roots.

“In a less race-conscious world, black fiddlers and white blues singers might have been regarded as forming a single southern continuum, and such collaborations might have been the norm rather than being hailed as genre-crossing anomalies. Indeed, it is arguably due to the legacy of segregation that blues has presented the most common interracial meeting ground, since, given a level playing field, many of the African American southerners we think of as blues artists might have made their mark performing hillbilly or country and western material. Ray Charles said, “You take country music, you take black music, you got the same goddamn thing exactly,” wrote ethnomusicologist Elijah Wald in his 2010 book, The Blues: A Very Short Introduction.

In a deleted tweet, he wrote, “Google: Lesley Riddle, Steve Tarter, Harry Gay, DeFord Bailey, and The Carter Family.”

“When you uncover the true history of country music, you find a story so powerful that it cannot be erased,” the singer tweeted later.

And in another, he stated, “The real history of country music is about people coming together despite their differences, and embracing and celebrating the things that make us alike.”

And he cleared up any confusion about his reaction by stating. “Just want to clear something up: my reaction at the AMAs had nothing to do with Megan Moroney!” She’s an incredibly talented, hard-working artist who’s doing amazing things for country music and I’ve got nothing but respect for her. I’ve seen some hateful comments directed at her today, and that’s not what this moment was about. Let’s not twist the message — she is amazing and someone who represents the country community in the highest light!”

Some people on social media, perhaps not familiar with The Carter Family, compared them to the trio of vampires in Sinners.

It’s unfair to The Carter Family and unfair to Coogler, whose film took a far more interesting approach to the issue. I understand why there is resentment towards white musicians making bank off a Black music form while the people who created it get nothing or get their work ripped off. The members of Led Zeppelin giving themselves credit for the lyrics of old blues songs is a particularly egregious example.

Some of that was due to the time and not knowing that some of those tunes weren’t just examples of traditional music with an author that was impossible to pin down, but songs whose composer was still among the living, like Willie Dixon. Doesn’t excuse it, but there are mitigating circumstances.

Musical borrowing is a complex subject; the blues and folk music are built on it, and it’s a staple of Western art music. Multiple Bach cantatas are based on scalar and sacred songs. Charles Ives and Béla Bartók both frequently made use of the songs of their respective cultures. Does it become an issue when someone is making a lot of money off of it, and someone else receives no compensation?

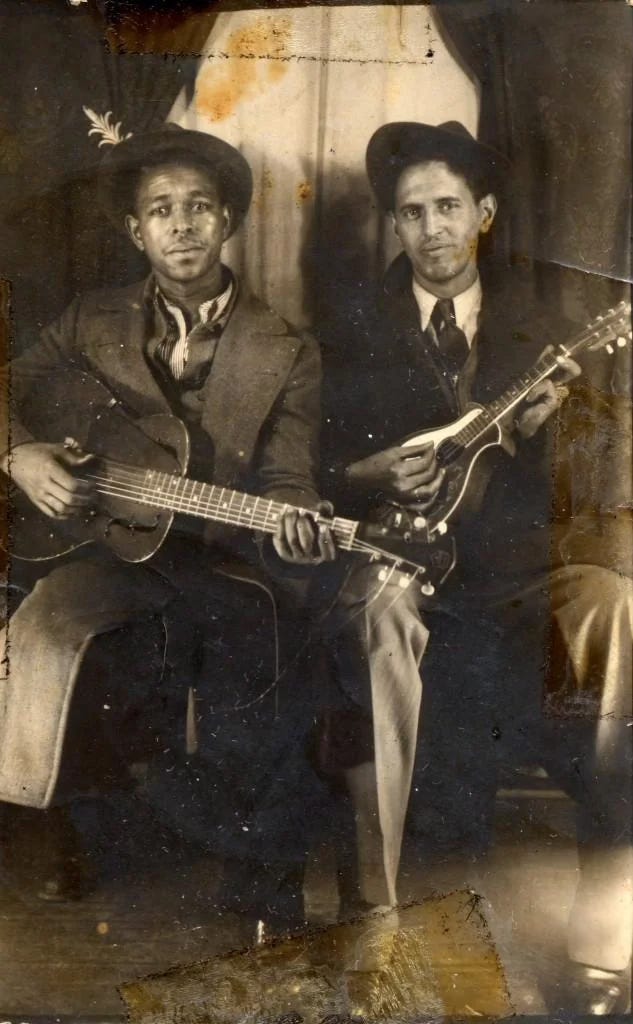

The full story of The Carter Family is much more interesting. Lesley Riddle, like W.C. Handy, had a true gift for remembering and transcribing songs. And he worked with A.P. Carter to find and preserve a lot of great music, songs that otherwise might have been forgotten. Songs that were part of the Roud Folk Index or were an outgrowth of the Black experience in America.

Riddle further shaped the sound of the Carter family by teaching guitar techniques to Mother Maybelle Carter and also teaching her songs he knew. He used a finger-picking style that he developed after losing two fingers to a shotgun accident. Before that, he lost the lower part of his right leg in an accident at a cement factory.

During his recovery time, Riddle learned guitar and how to play blues and gospel songs his uncle Ed Martin taught him. As a result of his new skill, he met other musicians in the area, such as Brownie McGhee and John Henry Lyons.

A.P. Carter was visiting Lyons when he met Riddle, and Carter was impressed by his singing and guitar playing. and Riddle joined him on several of Carter’s trips to find new songs.

Historian Elijah Wald notes in his 2010 book, The Blues: A Very Short Introduction, that the genres have common roots.

“From the outset, blues and country music were defined by racial segregation, and both genres’ histories continue to reflect a segregated view of an intertwining musical world. Folklorists and commercial recording companies—albeit for quite different reasons—tended to create a picture of the South that emphasized the separateness of black and white traditions. Early folklorists were attempting to document the oldest surviving styles and trace musical roots, so they focused on African American music that still showed ties to Africa, and on European American music that had obvious sources in rural Europe. Indeed, through the 1930s many folklorists considered blues too modern a style to be worth studying in either community. When the first comprehensive survey of African American rural folk music, The Negro and His Songs, was published in 1925, the authors concentrated on the most archaic-sounding material, gave secondary attention to songs that rural singers had “modified or adapted” from white or Tin Pan Alley sources, and did their best to avoid what they regarded as purely commercial forms, including blues.

The commercial record companies had a quite different agenda, since they were looking for salable lines of merchandise. But they quickly concluded that ‘Race’ and ‘hillbilly’ styles appealed to different markets. One difference was that white southerners were eager to buy music that recalled the past: The first country record lines were marketed as ‘Old Familiar Tunes’ or ‘Old-Time Tunes’ and concentrated on styles that reached back at least to the nineteenth century. Black rural southerners, by contrast, overwhelmingly favored music that suggested a freer, less constricting world than the one they had grown up in—for example, the bright lights of Memphis’s Beale Street and the booming black neighborhoods of Harlem and Chicago.

One result of this cultural split was that some records of older-sounding African American artists seem to have appealed principally to white consumers. Collectors searching the South for vintage 78s have reported that Mississippi John Hurt’s records were often found in white homes—and, as it happens, Hurt was originally recorded on the recommendation of a white fiddler, W. H. Narmour, who sometimes hired him as a back-up guitarist.

Despite segregation, Afro-and Euro-American string bands played a largely overlapping repertoire and sometimes performed in mixed groups. (Many musicians recalled such collaborations, though only a few were recorded.) Fiddles of various sorts are common to both Europe and Africa, and by the turn of the twentieth century the old-world styles had been cross-fertilizing for hundreds of years. The official segregation of the record lines concealed this overlap, to the point that black performers who recorded fiddle tunes were sometimes sold as white hillbilly artists, even though the same players were marketed in Race catalogs when they recorded blues or ragtime.”

What does it mean when someone outside of a culture attempts to take part in it? Is Elvis Presley’s take on Black music more valid than Pat Boone’s because he grew up in that milieu? What about a figure like Bob Dylan, a kid from the Midwest who loved and appreciated the blues, folk, and rock & roll? His breadth and depth of knowledge of these genres can’t be doubted. You can spend a whole lifetime trying to pick out all the allusions to obscure blues lines and folk songs throughout his entire body of work. There may be references to films, novels, or other things that Dylan scholars and fans don’t pick up on until years or decades of the fact.

It’s what makes his work, and by extension, roots music, such a rich and meaningful form of art. The history of so many different cultures, so many different lives and experiences are woven into it.

To fully understand it would require living multiple lifetimes, but even just the one, even with a limited viewpoint, makes it a rich, rich source. It embodies the American experience: full of subjugation, collaboration, love, hate, and everything in between.

To quote Walt Whitman, a frequent source of inspiration for Dylan, “Do I contradict myself?/Very well then I contradict myself,/(I am large, I contain multitudes.)”