Charles Ives In Groucho Marx’s Pajamas

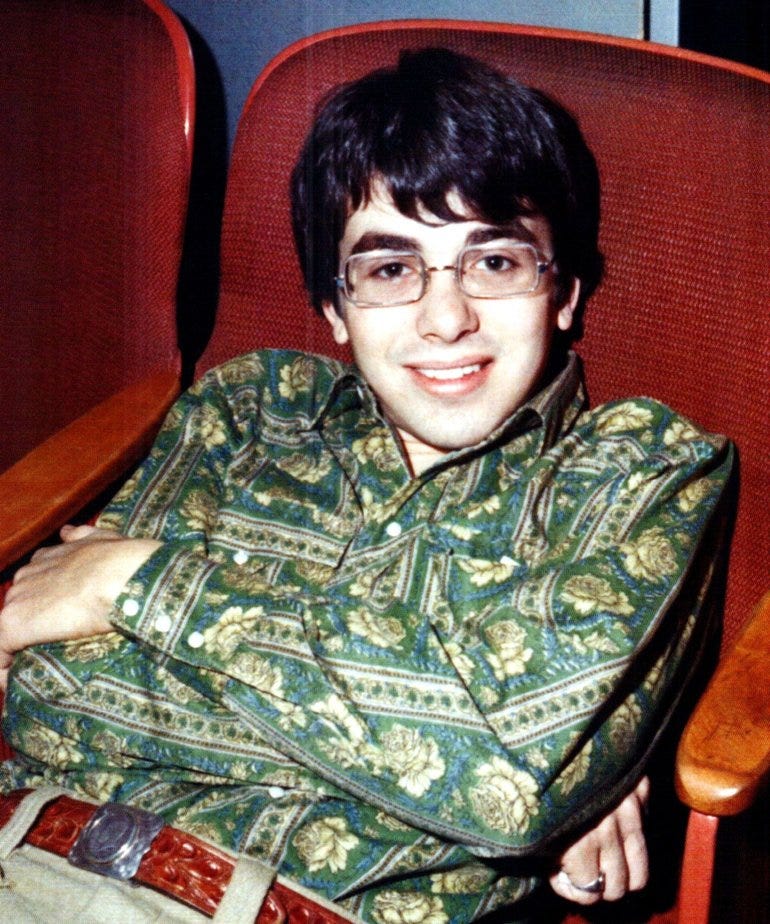

Geek rock is a term more associated with the likes of “Weird Al” Yankovic or They Might Be Giants than Van Dyke Parks, but, like those…

Geek rock is a term more associated with the likes of “Weird Al” Yankovic or They Might Be Giants than Van Dyke Parks, but, like those artists, Parks’s music features witty lyrics, allusions to popular culture and history, and quotation of specific melodies and styles.

I feel that Parks, along with Frank Zappa, is a godfather of geek rock. Like Zappa, Parks attracted, a small but devoted fan base, wrote music that examined the history and culture of the United States, and blurred the line between classical and rock music.

Parks is best known for his musical collaboration with Brian Wilson on the ill-fated Beach Boys album, SMiLE. Parks wrote the lyrics for the album. And the impressionistic, stream-of-consciousness quality of the lyrics did not meet the approval of noted curmudgeon Mike Love.

During the making of Pet Sounds, Love famously said to Wilson, “Don’t fuck with the formula! Love confronted Parks over the lyrics to “Cabinessence.” Love demanded that Parks explain the meaning of the line, “Over and over / the crow cries uncover the corn field.” Parks soon left the hostile environment.

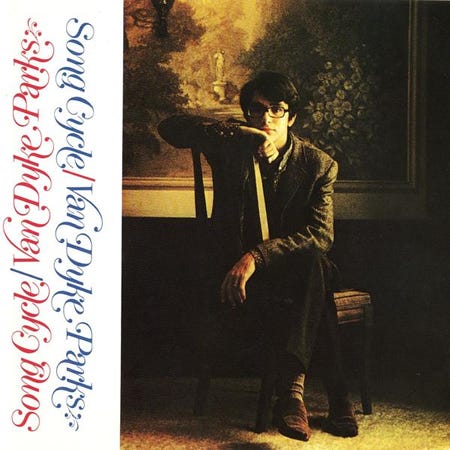

Parks signed to Warner Bros. Records and began work on his solo debut, Song Cycle. It was an album that would succeed where SMiLE failed, it would marry popular music with classical. And it succeeded, at least in a critical regard; a review of Song Cycle described it as “Charles Ives in Groucho Marx’s pajamas.”

It’s a fitting description, as Parks, like Ives, wrote music with a distinctly American theme and borrowed well-known melodies.

Song Cycle opens with “Vine Street,” a song Parks commissioned Randy Newman to write. Though not written by Parks, it contains features common to other tracks on the album, such as quotation of other melodies and the use of lyrics and sound to evoke a specific place.

The narrator of “Vine Street” is a folk singer down on his luck, the singer reminisces about living on Vine Street in the early days of his career. It features quotation of four melodies: “Black Jack Davey,” “Powerhouse,” “Ode To Joy,” and “The Entertainer.”

The song begins with Steve Young, a friend of Parks, singing “Black Jack Davey,” which lasts nearly a full minute.

At one minute and fifty seconds, the lower string voices begin playing a churning figure from Raymond Scott’s composition “Powerhouse.” Scott’s music was frequently featured in the cartoons of Warner Bros. to evoke the sounds of a factory. This is a reference to the album’s working title of Looney Tunes.

The next melody quoted is “Ode To Joy” from the fourth movement of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony. It occurs approximately two minutes and forty-four seconds into the song. It’s a reference to “Number Nine,” a pop version of “Ode To Joy” that Parks recorded as his second single. The song ends with a quotation from “The Entertainer” by Scott Joplin.

The fifth track of the album, “The All Golden” is the most Ives-like piece of the album. Parks uses lyrics, borrowed melodies, and sound effects to evoke images of Los Angeles and the post Civil War South. The song was inspired by the experiences of Parks and Steve Young had trying to make a living as musicians in Los Angeles. Both Parks and Young were originally from the South, the former from Hattiesburg, Mississippi and the latter from Gadsen, Alabama.

The first two verses of the song paint a picture of a starving artist. Parks makes use of several clever musical devices to portray hunger.

During the first verse, Parks makes use of the pentatonic scale on the line “he keeps a small apartment top an Oriental food store there.” It’s a clever musical pun as the pentatonic scale is frequently used in the traditional music of Asia.

Another clever musical gag occurs in the second verse, during first line, “Off the record/He is hungry,” one can hear horns. It’s a reference to “Cocktails For Two” by Spike Jones. It also calls to mind the noise of traffic in L.A.

The second verse features a line “I should think he’d fade away the way that Bohemians often bare the frigid air.” It’s a punning reference to the idea of hunger. When one hears the phrase frigid air, one also thinks of the Frigidaire brand of refrigerator. Parks emphasizes the idea of hunger by placing the pun close to the word bare, suggesting an empty refrigerator.

The miserable existence of an artist trying to make a living in a strange new world has parallels to the identity crisis of the South following the end of the Civil War. The South was devastated by the conflict and the agrarian economy of the South just couldn’t keep up with the more industrialized North. The infrastructure of the South was in ruins; partially to blame were the tactics of Union General William Tecumseh Sherman on his march to the sea. Sherman famously uprooted train tracks, heated them until they were pliable, and wrapped them around trees as way of demoralizing the Confederate army by cutting off their supply lines.

They were called Sherman’s neckties and Parks evokes this image by use of a train whistle. It’s also a reference to train at the end of “Caroline, No” on Pet Sounds. The train whistle serves another purpose as a transitional device: it indicates that the focus has shifted from the starving musician of the first two verses to the war torn south in the final three.

Parks further emphasizes the connection to the Civil War by quoting the melody of “The Battle Hymn Of The Republic” on the last three verses. Charles Ives quotes this tune in The Fourth Of July, the third movement of his Holidays Symphony, as well as in his song “They Are There!” It’s a clever joke as “The Battle Hymn Of The Republic” is associated with the Union Army and is based on the tune “John Brown’s Body.”

“John Brown’s Body” is about the death of abolitionist John Brown. The line “Nowadays them country boys don’t cotton much to one two three four” references the cash crop of the South: cotton. During “one two three four” the balalaikas play straight eighth notes, a clever musical joke.

Parks uses Porky Pig’s famous quote, “That’s all folks!” in the final verse of the song, yet another Looney Tunes reference.

During this last verse, the train whistle returns and there are sound effects suggesting that the train is pulling into a station near a seaport, setting up for the next track.

The sixth track of the album, titled “Van Dyke Parks” is a setting of “Nearer My God To Thee” by Sarah Flower Adams. The tune was allegedly the last song played on the RMS Titanic, before it sank. The tune for “Nearer My God To Thee” comes from a hymn titled “Bethany,” by Lowell Mason. Charles Ives quotes “Bethany” in his fourth Symphony.

In “Van Dyke Parks,” the train whistle has become the steam whistle of an ocean going vehicle. A lone male voice begins singing “Nearer My Go To Thee” and is soon joined by other voices, singing the same tune but in an entirely different key.

This is a compositional technique that Charles Ives employed in “Putnam’s Camp, Redding Connecticut,” the second movement of Three Places In New England. Ives wrote a program for the piece, a child wanders away from 4th of July celebrations and stumbles across two marching bands playing different tunes at the same time. To create this effect, Ives had divided the orchestra in two, each section played in key and meter different from the other.

“By restating the melody in another key, composer Parks sought to depict, across the water, this disengagement from the survivors of a sinking ship.” Parks intended it to be a metaphor for disconnection from issues of the day, such as Vietnam, politics, anti-intellectualism, and racism. Vietnam is emphasized by the use of battlefield sounds on the recording.

“The record was meant to illuminate these topics with this somewhat political commentary. I felt that a political consciousness was absolutely essential to anything that had any lyrical content. So that’s what this was all about. And the Titanic I thought was a pictorial opportunity.”

“Public Domain” is the seventh track of the album and is credited to Van Dyke Parks. This creates symmetry on four levels.

First: It’s a palindrome.

Two: Viewed on the sleeve of the album, the tracks form a chiasmus. Chiasmus is a structural technique used in poetry and music to emphasize relationships between aspects of a work. In this instance one draws a line from the title of track 6, to the writer of track 7 and from the writer of track 6 to the title of track 7 to create the Chiasmus. Chiasmus gets its name from the Greek letter, Chi, which resembles the letter X of the Latin alphabet.

Third: “Van Dyke Parks” closes the first side of the album and “Public Domain” opens side two of the album.

Fourth: “Van Dyke Parks” is non-autobiographical where “Public Domain” is autobiographical.

“Public Domain” touches on Parks’s time as music major at the Carnegie Institute and Parks described it as a “basic indictment of the patrician class, and the arrogance of the industry.”

Parks seems to have been somewhat unsatisfied with conservatory life, as he left the Carnegie Institute for Los Angeles in 1963. Parks establishes himself in this song as firmly against institutions that are restrictive and unreceptive to new ideas.

The 8th track of the album, “Donovan’s Colour’s,” is a keyboard tour de force, showcasing Van Dykes Parks’s prowess as a player. It’s a variations on “Colours” by Scottish folk singer Donovan. Parks recorded the song as a show of support to Donovan after seeing him treated poorly by Bob Dylan in D.A Pennebaker’s Dont Look Back.

In the film, Donovan visits Bob Dylan in his hotel and Donovan plays a song of his: “To Sing For You” for Dylan. During the performance, Dylan interjects “Hey, that’s pretty good, man!” There’s a hint of sarcasm in Dylan’s words, as Donovan song clearly owes a debt to Dylan’s early output.

At Donovan’s request, Dylan plays “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” and it’s painful to watch. The lyrics seem to be directed towards Donovan, who looks as though he wants the Earth to swallow him whole.

The song opens up with sound of a coin being dropped into slot, it evokes images of a giant music box or player piano. At one minute and twenty seconds, the song starts to slow down and builds a tension that finds its release at one minute and thirty-five seconds ,when Parks begins playing the tune like a ragtime piece.

It’s a callback to “Vine Street” which featured a quote from “The Entertainer,” a ragtime piece.

During this ragtime section, one of the keyboard instruments quotes “The Sailor’s Hornpipe.” It’s a tune that Charles Ives quotes in Violin Sonata No.2. “The Third Violin Sonata (called the Second) has a second movement based to a great extent, on the old ragtime stuff,” said Ives in a memo about the piece.

“The Sailor’s Hornpipe” can be heard in two Looney Tunes cartoons: “Buccaneer Bunny” and “Back Alley Op-Roar,” yet another call back to the album’s working title. The tune was often used in Popeye cartoons, an interesting bit of coincidence, as Parks would later collaborate with Harry Nilsson on the soundtrack for the Popeye film.

At 2:20, Parks begin playing the song as in a style reminiscent of Beethoven’s Für Elise. It’s also another reference to Pet Sounds, specifically the track “Here Today” which features a similar instrumental passage.

Song Cycle is a reference filled album that is more fully appreciated with a deeper understanding of its workings. It invites the listener to search out the tunes Parks borrowed and the references he made. What can be geekier than an artist who encourages his listener to acquire vast amounts of esoteric knowledge? Parks is a paragon of geek rock and Song Cycle firmly cements his legacy as one of the genre’s true greats.